THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's regular long-form series focusing on the biggest topics and most intriguing personalities in North American soccer. This week, senior editor Nick Firchau profiles the rise and sudden fall of Steve Snow, a Chicagoland striker once considered the greatest American goalscorer in the game. But an outburst during the 1992 Barcelona Olympicsand a subsequent knee injury helped keep him off the roster during the 1994 World Cup, when his former teammates headed down the path to American soccer royalty.

Ed. note: This article was originally published on May 9, 2014.

When Bruce Arena was inducted into the US Soccer Hall of Fame in August 2010, one of the first influences he cited that set him on his path to success came from one of the world’s most pedestrian of places: the wall of a Brooklyn sandwich shop.

The image of the 1950s-era Italian national team that hung in his grandfather's shop shifted the 10-year-old Arena’s focus from Mickey Mantle and the New York Yankees to a different game, and pushed him down the path to becoming one of the most successful soccer minds in American history.

There are no such photos on the wall these days at the suburban Indianapolis pizza joint run by Steve Snow, but perhaps there should be. There was a time more than 20 years ago when Snow was courted by Arena and nearly every other coach in the United States, earmarked to become the country’s greatest goalscoring hero.

In fact, had events played out differently, perhaps he could have been an iconic figure during the 1994 World Cup, when an entire generation of American players was embraced by adoring fans and kissed by the summer sun.

Of course, not many people know all that. Not his customers. Certainly not his employees, and not a soccer public that have recently devoured countless anniversary stories of 1994 and the engaging personalities that emerged like Alexi Lalas, Tony Meola and Eric Wynalda.

By all accounts, the American public would have loved Snow, too. He was a cocksure striker who demanded the ball, armed with the body of a beer-league player and ruthless finishing skills.

"I can play bad for 89 minutes," he once said, "but if I score in the 90th minute, it will be a good game for me."

Snow played on the same US Olympic team as Lalas, Cobi Jones and Chris Henderson in 1992 in Barcelona. There were other future heroes there as well – Brad Friedel, Claudio Reyna and Joe-Max Moore – but Snow was the man that made them go, scoring 10 goals in 10 Olympic qualifying games and earning the reputation as the best young goalscorer America had ever produced.

But by 1995, he was gone from the game, the victim of a bum knee, bad timing and an outburst in Barcelona that he’s said helped blacklist him from US Soccer for life. He was so furious, he couldn’t bear to watch his friends at the 1994 World Cup, and he’s lost touch with nearly everyone who played with him in 1992.

In fact, the greatest goalscorer of his generation has practically given up on the game entirely.

“For years, we would ask around if anyone had seen Steve or knew what was going on, and usually you hear stories about where a guy ends up,” Lalas says. “But with Steve, when it went, it went fast. He was like a shooting star. He literally fell off the face of the map.”

–-

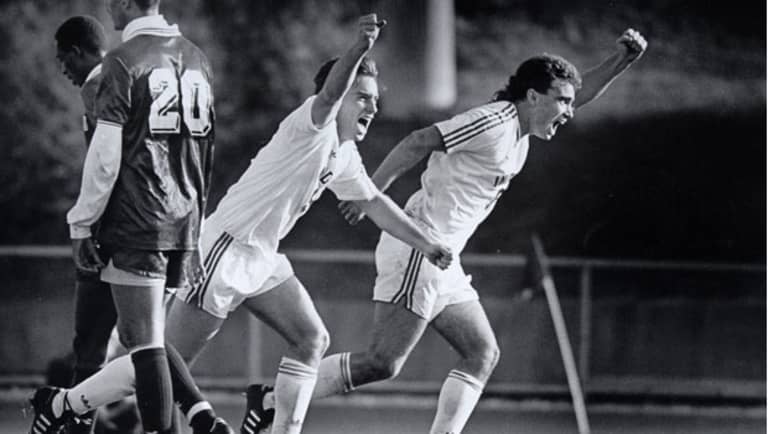

Steve Snow (left) was the leading scorer during the 1989 NCAA Tournament with the Indiana Hoosiers, but his stay on campus didn't last long. Pictured here with his brother Ken, Steve left school after one year. (Indiana University)

–-

In 2014, it’s tough to imagine an athlete can accomplish anything without a cell phone in the crowd or YouTube to ensure it was done. But for a professional soccer player in America 20-25 years ago, it was more than likely he toiled for tidbits in the local newspaper, with no video footage at all of what he’d done.

In Snow’s case, the vault is completely bare. For proof, a request to US Soccer for footage of even a single goal sent an intern into the archives at the federation’s headquarters in Chicago on an ultimately hopeless mission.

“Combed through our old video library here and there wasn’t much doing beyond ’96, other than ’94 World Cup stuff,” reads the response. “Wish we had something.”

Luckily, the anecdotes speak for themselves.

Originally from the Chicago suburb of Schaumburg, the 5-foot-8, 165-pound Snow was one of the most heralded players in Illinois high school history. He scored 111 goals in four seasons at Hoffman Estates High School and was the Parade Magazine High School Player of the Year in 1988. His record of 49 consecutive games with a goal still stands in the state record books today, 25 years after it was set.

“In our area, everyone knew who Steve was and how good he was. He was unstoppable,” says USMNT legend Brian McBride, who attended nearby Buffalo Grove and was a year younger than Snow. “He had great feet in tight spaces, and in that day and age, he had the quickest release of anyone I’d seen. And he was deadly.”

- THE WORD: Inside the mind of an MLS goalscorer

Never considered an exceptional athlete, Snow made due with a scorer’s instinct and a scrappy demeanor on the field built over time by playing in the shadow of his older brother Ken, also a star prep forward. Steve would often play on youth teams one or two years older than his and took his requisite lumps along the way, eventually developing a feisty and confrontational personality that earned him criticism throughout his career.

“He was a tough [expletive] on the field,” says Ken, who himself scored in 47 straight high school games and went on to win two Hermann Trophy awards as the nation’s top college player. “Everybody knew they had to watch him, and he never backed down from anybody. So yes, there were some confrontations.”

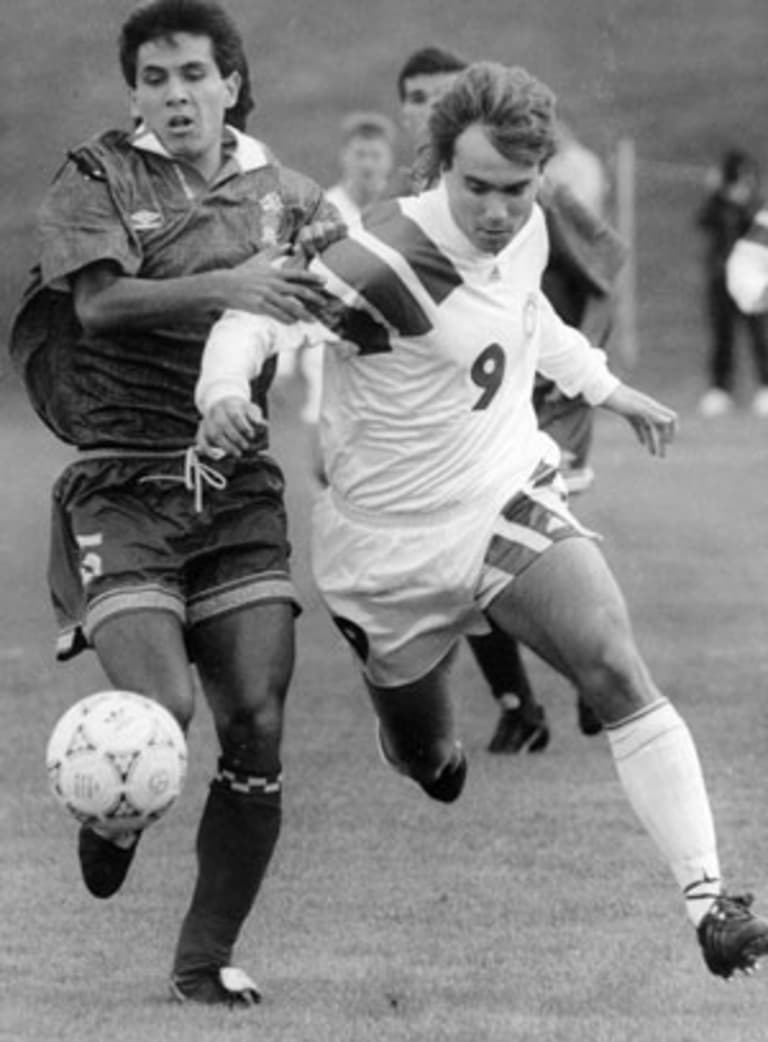

Steve Snow’s finishing skills landed him on the US youth level radar early and kept him there, and he eventually played a vital part in the team’s qualification for the 1989 Under-20 World Cup in Saudi Arabia. He scored five goals in seven qualifying games and another three in six games at the World Cup as the US placed fourth, still the best finish in the program’s history.

Considered perhaps the best goalscorer of his generation, Steve Snow (9) was a star in high school and at the US youth levels. "In our area, everyone knew who Steve was and how good he was," says former USMNT striker Brian McBride. "He was unstoppable." (US Soccer)

While in Saudi Arabia, Snow was approached by a representative from Belgian first-division club Standard Liège, a rare move by a European club for that era. American-born players in Europe were something of a rarity in the late 1980s, but Standard wanted Snow for the same reason Arena wanted him at Virginia and countless other coaches wanted him on their campuses.

“From 1985-1989,” says Henderson, “he was the best forward in the country. He was the best goalscorer I’ve ever played with.”

- THE WORD: The legacy of the USMNT and David Regis

Snow eventually spurned Standard’s offer and chose to join his brother Ken at Indiana University, but he didn’t last long. He was the leading scorer at the NCAA Tournament in 1989 and helped guide the Hoosiers to the semifinals only to leave college after his freshman year and pursue his career in Europe.

And although it was a tougher slog for Snow in Belgium – he was immediately loaned out to a third-division team, where he was homesick and his offensive numbers suffered – he re-emerged as a force for the US during the 1991 Pan-American Games, a primer for the Barcelona Summer Olympics. Snow was the tournament’s top scorer at the Pan-Am Games and helped lead the Americans to the title, setting the stage for a dominant run through Olympic qualifying in the spring of 1992.

Snow scored nine goals in the team’s final five qualifying matches – a stretch that included two wins over Honduras and one each over Canada and Mexico – as the US clinched the top spot in CONCACAF qualifying. They’ve never managed to duplicate that success since.

He scored multiple goals in three games during that stretch, including a hat trick in a 4-3 win over Honduras in St. Louis when he had just three shots the entire game. All three went in.

He also scored two in a win over Mexico that sealed the US team’s spot in Barcelona and another two in a win over Canada in Bloomington, where he’d starred in college three years before.

After that match, reporters hounded Snow about his chances of making the 1994 World Cup team, just two years away.

“I would think they would want me on the team,” Snow said at the time. “I think I’m the best goalscorer the US has ever had. If they don’t have me on the team, the US is going to have a tough time scoring.”

–-

Snow scored nine goals in the US team's final five Olympic qualifying matches in 1992, making him the top team's top scoring threat heading to Barcelona. Said Snow: "I think I’m the best goal scorer the US has ever had." (US Soccer)

–-

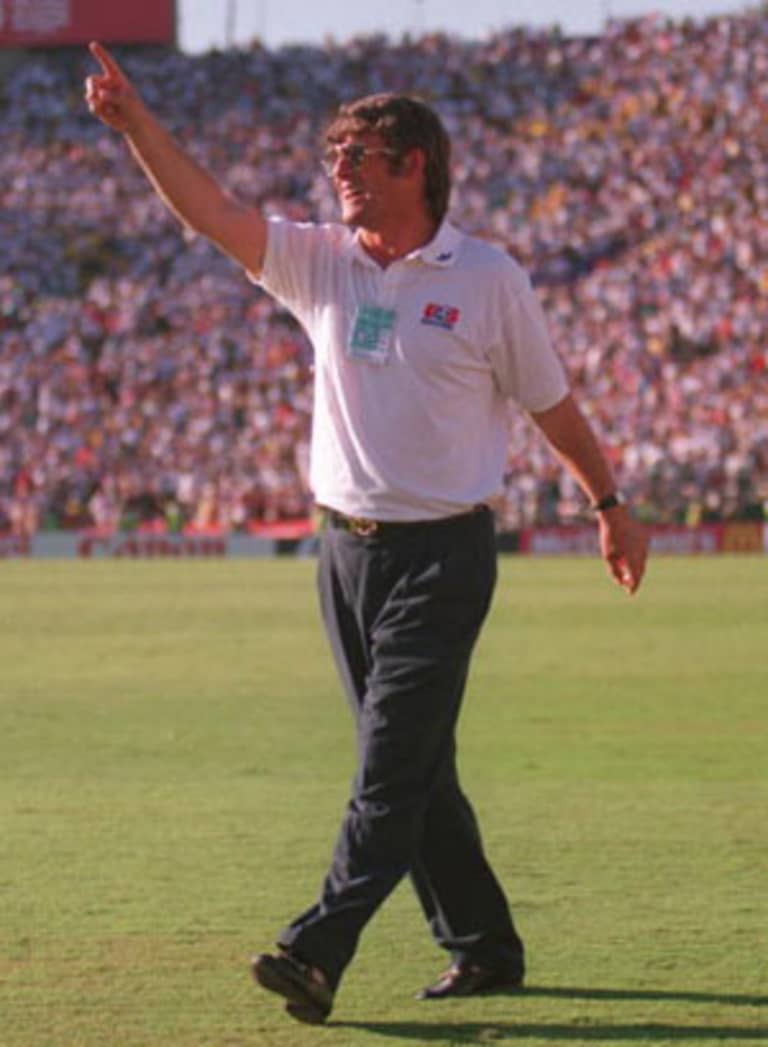

There are few personalities in the history of US Soccer quite like Lothar Osiander, the German-born head coach tasked with helping lift American soccer to new heights in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Born in Munich near the dawn of World War II, Osiander emigrated to California as a teenager and played and coached in San Francisco’s semi-pro leagues before he emerged as a top tactics coach during the 1970s.

He eventually coached the US national team for a short period from 1986-88 before he was relegated to Olympic team coach ahead of the Barcelona games. With quick wit and scathing public criticism of his players that is exceedingly rare in today’s game, Osiander's personality was a tough one to muzzle for the team's public relations staff.

US Olympic coach Lothar Osiander was one of the most quotable figures in US Soccer history, and didn't shy away from public criticism of his players. "He’s a cocky little twerp," Osiander once said of Snow, "but he’ll get you a goal.” (Getty Images)

“Our team is too homogenous,” Osiander once observed of the Olympic team. “They’re all the same age, all college students, all middle class. They all go to good schools, read the same books, like the same music, probably chase the same type of women. Everything’s equal. It’s flat as a pancake.”

Snow was a particular favorite of Osiander’s when it came to comments in the press, and while Osiander praised Snow at times, he also chastised him for not training hard, for his lack of defensive work and even for his love of pizza, which Osiander claimed Snow could eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner if given a choice.

The lasting comment that reporters seized on and repeated in the lead-up to the games, however, defined a taxing and symbiotic relationship between the two men.

“If he couldn’t score, he’d be sitting on someone else’s bench, not mine,” Osiander said in April 1992. “He’s a cocky little twerp, but he’ll get you a goal.”

There was plenty of truth to that. While the bulk of his teammates were stars in college – Lalas at Rutgers, Reyna at Virginia, Moore, Jones and others at UCLA – Snow was on the books with a club in Belgium and had trained with English Premier League club Tottenham Hotspur.

And after his dominant performance during the qualifying rounds, Snow strolled into Olympic camp ahead of the Barcelona games with the lion’s share of the team’s success on his shoulders.

“He had a beautiful arrogance,” says Lalas, who roomed with Snow in Barcelona. “I had been around enough goalscorers by that point to know that it was a necessary evil, and you had to grin and bear it to get those valuable goals.

“We knew that when we got on the field, there was a really good chance that we were already up 1-0, because he was going to find a way to score a goal.”

Fate dealt the American team a relatively tough hand in the group stage at the Olympics, where they were drawn with Poland, Kuwait and, in the opening match of the tournament, Italy. The two sides were scheduled to face off at the historic Camp Nou stadium in Barcelona on July 24, the night before the opening ceremony.

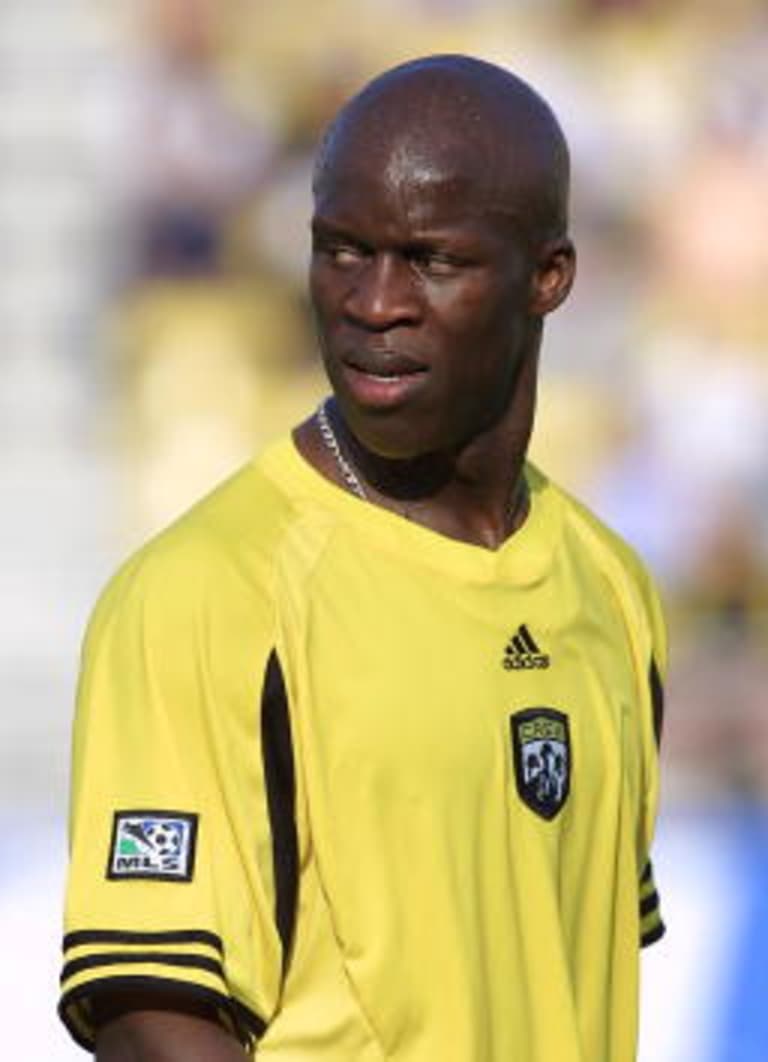

Former Columbus Crew striker Dante Washington was one of the top US goalscorers in the buildup to the 1992 Olympics, and an exact opposite to the playing style of Snow. (Getty Images)

"Not long ago, this would have been a very bad game," FIFA general secretary Sepp Blatter said at the time. "Three years ago, it would have been bad for the United States and bad for soccer. But now we are looking quite forward to it."

Osiander and the American players met the media in Barcelona three days before the opening game, and reporters quickly pounced on the storyline between Snow and Dante Washington, a 21-year-old star striker at Radford University.

While Snow had earned most of the accolades during qualifying, Washington had done his part, too, scoring seven goals in 10 matches, including the game-winner of a 4-3 victory for the US over Honduras in front of 25,000 fans in San Pedro Sula.

Former Baltimore Sun reporter Bill Glauber jumped on the storyline and described Snow as a “college dropout” who was “like some sort of Lenny Dykstra in shorts – snarling, brooding, demanding to be heard and seen.”

And Washington, he wrote, was “a college star who talks of politics and teamwork … a part-time player with a world-class shot.”

Although the two had played together for the US on numerous occasions leading up to Barcelona, there was a thought that Osiander would take a conservative approach against the talented Italians and employ a more defensive strategy, hoping for a draw in the team’s opening game.

When they weren’t bunkered down, using the speedy Washington instead of Snow would allow the US to possibly catch the Italians on a counterattack. If the team could get a draw in the opener against mighty Italy, wins against Kuwait and Poland weren’t out of the question, and the Americans would survive the group stage.

“Hopefully, they'll be friendly with us,” Osiander said of the Italians. “Hopefully, they'll remember Christopher Columbus discovered America, and we are discovering Italian soccer. So I hope they let us discover it without crucifying us."

--

George Vecsey still remembers the way Steve Snow marched off the field and down the tunnel at Camp Nou, fixated on the American media.

“He’s coming up the tunnel, and he’s fuming,” says Vecsey, the longtime New York Times sportswriter. “Then he sees us, and, well, he just starts going off.”

Relegated to the bench for the entirety of the team’s match against Italy, the outspoken Snow promptly let fly a public tirade most athletes tend to bottle up, even when they’ve been mysteriously left out of the lineup in the biggest game of their lives.

“This team cannot play at all without me,” Snow barked at the reporters. “This team wouldn’t be here without me … This is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever seen. [Osiander] didn't think we could win the game. He wanted to come out with a 0-0 tie. He thought [Italy] were gods.”

Osiander had indeed opted for a more defensive strategy against the Italians, giving Washington the start in hopes that his speed could turn the game in a flash. It didn’t, and the Americans were badly outplayed in the first half and fell into an early 2-0 hole before Moore scored in the second half to salvage a respectable 2-1 loss.

US captain and defender Cam Rast (2) attempts to avoid Italy's Alessandro Melli during the opening game of the Barcelona Olympics. Melli scored in the first half and the Americans eventually lost 2-1 before Snow publicly criticized Osiander to the media after the game. (Getty Images)

The plan, Washington says now, was for him to start and tire out the Italian defenders before Snow came on in the second half. After the Americans went down two goals in the first 20 minutes Osiander swapped in the playmaker Moore for defender Troy Dayak, and then midfielder Mike Huwiler suffered a hamstring injury early in the second half. That injury forced Osiander’s hand to make a defensive substitution – Virginia’s Curt Onalfo got the call – and the team was out of subs before Snow ever got off the bench.

“I can't even face him. I'm so mad at him, it's unbelievable,” Snow told the press. “I've never been screwed worse than this in my life. It's the worst thing that has ever happened to me.”

Osiander promptly fired back, telling the media that he started a lineup focused on countering Italy’s skill with speed and defense, neither of which Snow had.

“He took it as a personal attack because he doesn't think much,” said Osiander, who insisted Snow cursed at him when he saw the starting lineup. “If he wants to play at all, he'll have to apologize. He is a team member, and he has to adhere to team rules.”

Snow refused.

“I'm not about to kiss up to him just so I can play,” he said. “My personality is part of what makes me such a good goalscorer.”

Snow’s comments weren’t entirely unexpected, given his standing with Osiander before the Olympics. He’d nearly been kicked off the team in January, when his attitude clashed with coaches and teammates. He’d drawn Osiander’s ire for being out of shape or disinterested in past camps, and he was disqualified for the semifinals in the Pan-Am games for fighting. He insisted Osiander had a grudge against him.

The comments in Barcelona, however, drew a line that his teammates insisted Snow shouldn’t have crossed. While a number of the players agreed that benching Snow in the team’s biggest game to date was a mistake, it was tough to support Snow’s public catharsis with two games left in Barcelona and some hope to advance past the group stage.

“In hindsight, Steve probably didn’t react the right way or handle that the best,” says Mike Burns, a 1992 teammate and now the general manager of the New England Revolution. “I give Lothar some credit there actually, because some other coaches would have sent him home right away.”

Snow insisted at the time that his teammates supported him after the benching, an idea Lalas balked at with the press.

“Steve is my friend,” he said. “Heck, I'm rooming with him here. He is a great goal scorer and a big-game player. But he has a lot to learn about handling himself in private and public.”

Despite his steadfast objections to Osiander’s decision, Snow eventually relented and issued a public apology before the second game three days later.

The US went on to beat Kuwait 3-1 and draw eventual silver medalist Poland 2-2 on July 29 to close out the group stage, but they failed to advance to the knockout round. Snow scored a goal in each game.

–-

The US national team spent more than a year ahead of the 1994 World Cup in Mission Viejo, Calif. Said midfielder Chris Henderson (middle): "Unless you were one of the guys in Mission Viejo, there wasn’t really a place to go." (Getty Images)

–-

Snow returned to Belgium following the Olympics on a loan from Standard Liège to first-division side FC Boom and scored four goals in his first seven games, but he tore the ACL and meniscus in his left knee during a workout in the fall of 1992.

By the time he was able to play again, Boom had been relegated from Belgium’s top flight, and Standard opted to have him train with their reserve team. Unable to crack Standard’s first team or find a deal elsewhere in Europe, Snow toiled with the reserve squad until late 1993, when the team cut him loose.

A number of his former Olympic teammates, meanwhile, had been placed on the fast track to the World Cup. US national team head coach Bora Milutinovic had already assembled the group that would make up the bulk of the 1994 roster and begun working with them tirelessly in Mission Viejo, Calif. The group – which included Lalas, Jones, Reyna, Burns and Henderson – played 29 international matches across the globe in 1993 in preparation for the World Cup.

Milutinovic’s strategy was simple. With no top-flight league in place for his players in the United States, US Soccer could operate the group much like a professional club team, including compensation from the federation.

“Unless you were one of the guys who signed with US Soccer who spent that time in Mission Viejo, there wasn’t really a place to go,” says Henderson, who was later one of the final cuts before 1994. ”There was a hole there. You could scrap in a five- to six-month league somewhere or play indoor, but a lot of guys missed it.

“And Steve was one of the guys who missed it.”

With no call from US Soccer for the Mission Viejo camp, Snow returned home to Chicago. He signed a deal with the Chicago Power – a local indoor team his brother Ken had played for since 1991 – and the local press celebrated the homecoming of an Olympic hero, but Snow knew better. It was a dead end.

"I haven't played indoors since high school,” he told the Chicago Tribune, “but I'm willing to give it a try.”

Snow scored 30 goals in 43 games over two seasons with the Power, but by 1995, he was battling lingering knee issues and his career had stalled. While his Olympic teammates thrived during the World Cup the summer before, Snow hardly watched any of the festivities. At just 24 years old, he quit the game.

Major League Soccer opened the next spring and Wynalda – the cocky, 27-year-old forward who starred for the US team two summers before – scored the first goal in league history.

–-

Now a husband and father of two teenage girls, Snow runs his own restaurant and catering business in suburban Indianapolis. He quit playing in 1995 and has largely stayed away from soccer ever since. (Phillip Taylor)

–-

There was a time when Steve Snow worked 70 hours a week as a small-business owner, even if he was unsure his company would last another week.

He founded Roselli’s Pizza in the College Park neighborhood of Indianapolis in 1995 and eventually moved it to a larger location in suburban Carmel, where it’s been a success since 2003. Now a father of two teenage girls, he shows up at 8 am every day and is typically gone by noon, often working out with his brother Ken at a nearby gym or attending his daughters’ dance recitals or gymnastics meets.

There is very little soccer in Snow’s life at all these days, and that’s by choice. He’s never coached. Never held striker camps in the Chicago suburbs, like his brother. Never sought out the limelight for what he accomplished in 1992, or why his career exploded shortly thereafter.

“I don’t know if he even thinks about it,” Ken Snow says. “We never talk about soccer. He’s just past it.”

That’s up for debate. It’s clear that although Steve Snow has effectively phased soccer out of his life, he still bristles at the events in Barcelona and what followed leading up to 1994. He remembers the Italy match as clear as ever and insists he has never spoken with Osiander since their public falling out.

“I had never really ever had a problem with coaches,” Snow says. “But with Lothar, it was a strange relationship. It felt like he didn’t want me to successful.”

Would Snow have even made the World Cup team in 1994 under head coach Bora Milutinovic? Some have their doubts. Says Dante Washington: "I don’t think Bora would have taken his [expletive].” (Getty Images)

Osiander – who was let go by US Soccer following the 1992 Olympics and eventually worked short head coaching stints with both the LA Galaxy and San Jose Clash – did not respond to repeated requests for an interview for this article. He currently serves as a consultant and coach for a youth soccer program in San Ramon, Calif.

Snow says than when he spoke out following the Italy game, it raised a red flag in American soccer circles that he was a potential troublemaker for coaches, and he was not to be trusted on a roster. There were other indiscretions on his résumé, too – the fight at the Pan-American Games in 1991, stories of hard partying on the road and a stubborn sense of entitlement that rubbed other players the wrong way – and he says it all added up to US Soccer effectively shutting him out of the program entirely after his knee gave out in 1992.

“Barcelona wouldn’t have mattered at all if I hadn’t gotten injured afterward,” he says. “But when I got hurt, anything I had ever done that was negative came out as a reason for them to pass me over. And if the national team says you’re done, you’re done. There was nothing else I could do.”

Adds his brother Ken: “He wasn’t the nicest guy to people. When you’re on top, that’s OK. When you’re not, and you need something, nobody is there to give you a chance.”

It’s also up for debate if a healthy, headstrong Snow would have made the US roster in 1994 at all. Three weeks before the World Cup, Milutinovic called in seven foreign-based players to the camp in Mission Viejo that included the 1990 World Cup veteran Wynalda and Dutch pro Earnie Stewart, who partnered up top for the team in all four matches at the World Cup.

While Snow epitomized what Milutinovic spoke of when he often professed his love of players who could “smell the game,” he would have been forced to change his game a bit to fit in with the Yugoslavian head coach’s scheme.

And there’s little doubt that Milutinovic would not have tolerated any of the insubordination Snow had shown with his previous teams.

“The national team camps were extremely hard to get into,” says Washington, who earned six senior team caps between 1991-1997. “And honestly, Steve was a bit of an a------. I don’t think Bora would have taken his [expletive].”

Snow says he's lost track of most of his 1992 teammates, and he's devoted his life to the success of his business. "Everything else had been taken away from me," he said. "The restaurant had to work.” (Phillip Taylor)

What’s more likely is that a healthy Snow would have thrived during the early days of MLS, likely in competition with his peers Wynalda and McBride. Described by those who knew him as a player with the playmaking instincts of former MLS great and World Cup goalscorer Clint Mathis and the finishing abilities of 2014 World Cup hopeful Chris Wondolowski, Snow’s skills would have almost certainly translated to a league finding its footing in 1996 and searching for stars.

“I don’t think we ever got to fully see what Steve Snow could do,” Lalas says. “If Steve came out in 2014 in MLS, he would score bunches of goals, and he would do it with a flair that I don’t think we see a lot.”

But all that doesn’t matter much now to Snow, who says he’s too busy to spend much time thinking about the past. He says he’s lost track of many of his 1992 teammates and he’s devoted to his restaurant, which nearly sunk him in the late 1990s.

“I couldn’t stand the way things ended – I didn’t want to hear anything about soccer,” he says. “Especially during those first few years with the restaurant. That’s probably what made me stick out those first few years, which were tough for us. It was all I had. Everything else had been taken away from me. The restaurant had to work.”

If you call Roselli’s to order a pie and get placed on hold during a busy Friday night, you get greeted with a voice message that asks you to picture yourself there, the ballgame on the television, your kids ecstatic and you enjoying it all with a cold beer in your hand.

It’s the image of a lifestyle not so different from the one a young Bruce Arena enjoyed back in Long Island years ago, the the son of a butcher and a school bus driver. Before soccer took hold. Before success came calling.

Cold beers. The ball game on the tube. A fine suburban life.

“There’s obviously the ‘what if’ part here for Steve’s story, but there’s the ‘what actually happened’ part, too,” says Burns. “And the ‘what actually happened’ part is that the kid scored a lot of goals.

“But,” he adds, “the ‘what if’ part would have been nice to see.”