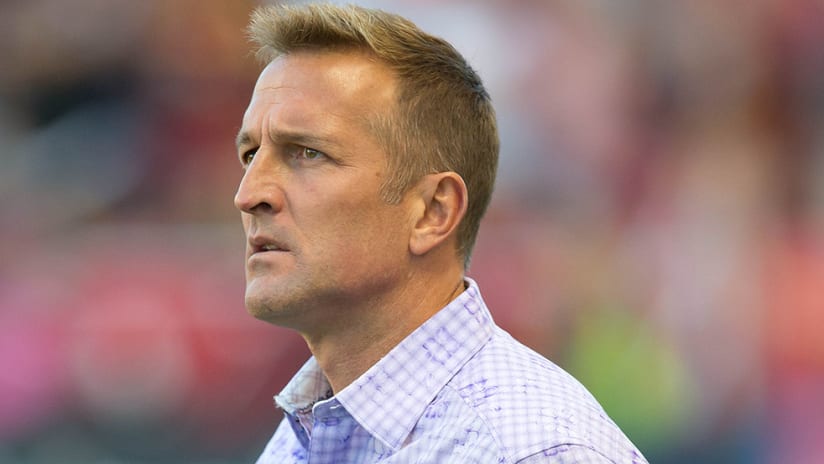

Jason Kreis and the United States Under-23 national team are finally approaching the home stretch.

As the U-23s train at IMG Academy in Bradenton, Florida this week, Concacaf confirmed the rescheduling of its Olympic qualifying tournament, slated to unfold almost exactly one year after it was originally scheduled before being abruptly called off due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

That clarified the team’s path to the Summer Games in Tokyo, a goal that’s become something of an odyssey. That's not only for the current group but the entire USMNT program, which is nursing a 12-year-long Olympic qualification drought and the various costs that accompany that painful string of setbacks.

“It feels like with this qualification process, it's been one challenge after another,” Kreis, the team's head coach, told reporters on Tuesday.

Can this group ultimately earn one of Concacaf’s two berths in Japan? Let’s examine a few topics that figure to have a big influence on that.

How many first-choice call-ups will Kreis get?

With young American talent earning more first-team minutes than their predecessors both at home and abroad, Kreis and his staff have a deeper and more experienced player pool to consider. But as is always the case with the Olympics – just a youth tournament in the eyes of FIFA – the lack of mandated club releases for call-ups will likely significantly restrict their options when it’s time to build the roster for March.

Clubs overseas are notorious for declining Olympic call-ups, even for players who aren’t key members of their first team, while MLS and USL have generally been more willing to let theirs take part. That could be evolving, though, as youngsters become more important contributors. Kreis warns that this topic is very much a case-by-case situation.

It’s primarily the job of USMNT general manager Brian McBride to lobby clubs for releases. There’s hope that the growing transfer market for US players will help convince many that everyone stands to benefit from the experience and visibility offered by the Olympic stage.

“Every club has different motivations and different ways that they look at national team exposure, especially youth national team exposure,” said Kreis. “We think that these are tremendous opportunities for the players for two reasons. Number one is obviously to represent your country and experience soccer on an international level, just the experiences that these players get are, I think, quite unique, and really special for players to experience.

“And number two … you get these players in front of more scouts that are at different games and being exposed to different coaches watching these games, or different people that are coming from clubs to watch these games. And now you've certainly, I think, increased the market value of the player. And I think we're getting more and more of an understanding and appreciation for that, especially with domestic clubs here in MLS.”

Will the burden of history weigh on the current squad, or inspire it?

It’s never been easy to qualify for the Olympics, and the experience seems to be high-risk/high-reward.

Taking part in the main event was a career springboard for the likes of Jozy Altidore, Stuart Holden and Sacha Kljestan in 2008, as well as Landon Donovan and Josh Wolff in 2000. Conversely, Jurgen Klinsmann later spoke evocatively of the nasty hangover, both individually and collectively, that afflicted the talented crop that stumbled during the 2012 cycle.

The fortunes of the U-23s can also be a canary in a coal mine for the senior national team. Many have argued that the knock-on effects of the ill-fated ‘12 and ‘16 Olympic campaigns was reflected in the USMNT’s 2018 World Cup qualifying woes.

For now at least, it appears that this year’s group isn’t thinking too much about the past in any direction.

“I think all of us know the history of the United States in terms of qualifying for the Olympics, but that hasn't been our focus at all,” Atlanta United center back Miles Robinson said in a media call Thursday. “The focus has been on us as a group getting better day by day. And that's the main goal for this whole cycle, it's always been to qualify for the Olympics, and I think if we continue to have great sessions like we have already, that can definitely be something that happens in the future.”

Can the US manage a tricky Group A assignment?

Concacaf currently uses a straightforward qualifying format with a round-robin group stage comprised of two four-team groups. The top two finishers in each group advance to the all-important semifinals, where a win books both a final berth and an Olympic place.

Past US U-23 campaigns have ended (or in the case of the 2016 cycle, been railroaded toward eventual doom) with agonizing semifinal losses to Mexico or Honduras. This year it’s a bit different.

That’s because Honduras have moved ahead of the US in the formula, based on past performance in this competition, by which Concacaf seeds participants. So the young Yanks have been drawn into Group A with hosts Mexico, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic – about as close to a “group of death” as you’ll find in this part of the world.

Though the island nation are rising in the soccer world, the DR will still be seen as a bankable three points for all three of their counterparts. Meanwhile no one ever wants to have their hopes hinge on beating El Tri on Mexican soil (and remember, Guadalajara sits about a mile above sea level). So that makes the meeting with Costa Rica absolutely massive for Kreis & Co., and goal differential may well come into play in the final reckoning.

If the original slate carries into 2021, the US would open against Costa Rica, then face the DR before concluding versus Mexico. We’re still awaiting the confirmation of such details for the rescheduled edition.

An optimist might argue that on the bright side, survival would lead to a less daunting task in the semifinals. That's where the US would face one of the top two finishers in Group B – composed of Canada, El Salvador, Haiti and Honduras – for a ticket to Tokyo. We’ll have to see if such an outlook makes sense come late March.