THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's regular long-form series focusing on the biggest topics and most intriguing personalities in North American soccer. In this installment, Pablo Maurer digs in to the forgotten history of Team America, a failed bid to improve the fortunes of the United States national team – and perhaps capture World Cup hosting rights – and reinvigorate the NASL.

In 1992, with no top-flight professional league in place and just two years away from hosting the World Cup, the United States Soccer Federation assembled their men's national team in Mission Viejo, California, for a two-year-long training camp.

The group that banded together in Mission Viejo – previous unknowns such as Alexi Lalas, Tony Meola, Marcelo Balboa and Eric Wynalda – became household names, defying the odds to stun Colombia in the World Cup group stage before narrowly losing to eventual champion Brazil in the Round of 16.

A decade earlier, across the country in Washington, D.C., the federation had taken a similar gamble, one that's since been relegated to the shadows of U.S. Soccer history, a forgotten footnote to the 1994 team's fairytale run.

In 1983, with the US' largest pro soccer league in a full-on tailspin and its national team mired in near-permanent irrelevance, the North American Soccer League and the USSF became strange bedfellows, unlikely teammates on an improbable team.

Team America.

Ronald Reagan was never much of a soccer fan.

Yet in May of 1983, the 40th President of the United States of America stood in the Rose Garden of the White House, surrounded by a group of soccer players dressed in red, white and blue. Reagan, always a ham for the cameras, stepped to the podium and delivered a few remarks.

"I was worried that they might be attracted by the expanse of the South Lawn," he joked, "that's why we turned the water on out there."

"The Gipper" rambled on, digging back into his acting days to tell a story about Knute Rockne and football of the gridiron variety. The soccer team presented the commander in chief with an autographed ball and set of warm-ups. "You can hold onto this when we win the World Cup," a team official told Reagan.

The ceremony had all the pomp and circumstance typically associated with war heroes and foreign dignitaries. A week earlier, Reagan had welcomed German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. The following week, he'd welcome the Crown Prince of Jordan. On this day, though, the newest professional sports franchise in the nation's capital, Team America, got the presidential treatment.

Robert Lifton with President Ronald Reagan (courtesy of Alan Merrick)

The businessman who handed Reagan the ball – and arranged the visit itself – was Robert Lifton, and only moments earlier, he'd met privately with Reagan in the Oval Office. "I tried to make sure he understood that this was a soccer team, and not some baseball team," Lifton told MLSsoccer.com from his home in New York earlier this summer. "There was a fear in my mind, which continued as he was speaking, that he might think we were some other kind of team."

Reagan hardly could have been blamed for a potential mix-up. At the time, club soccer in the United States was quickly falling off the map; the days of Pelé romancing sold-out stadiums had passed, replaced by vast expanses of empty seats in oversized venues. At the NASL's peak in 1978, the league counted 24 teams among its ranks. By the time the 1983 season rolled around, only 12 remained, and attendance had been steadily decreasing for three years. Amidst talks of a work stoppage, the league was reportedly losing $25 million dollars a year.

On the international front, things were even bleaker. The US hadn't qualified for a World Cup in more than 30 years — they hadn't even come close. The national team hadn't played a game in 1981, and they'd gathered for a solitary international friendly in 1982. The organization consisted of only a handful of full-time staff, led in part by Executive Vice President Werner Fricker, who'd climb the ranks to President the following year.

Out of the NASL's headquarters in New York City came an attempt to kill two birds with one stone. League President and CEO Howard Samuels, who would later go on to become the NASL's final commissioner, hatched a near unheard of idea. He'd collect the top American talent from teams across the league to form an American super club that doubled as the US national team in training. The club, Samuels hoped, would inspire the imagination of the American fan, providing the league with a much-needed infusion of interest and cash.

U.S. Soccer also stood to benefit from the arrangement. As hosts, the US automatically qualified for the Round of 16 at the 1984 Olympics. More importantly, the 1986 World Cup hosting rights were up for grabs after host nation Colombia backed out, citing financial instability. If the US could demonstrate a commitment to the game at an international level, perhaps the tournament – a lifeline the sport desperately needed – could be hosted on American soil.

That's where Lifton, the businessman with Reagan's ear, came in. Samuels approached the New York-area entrepreneur with his pitch, and Lifton — a renaissance man whose previous ventures included banks, hotels and entertainment ventures, but never a sporting investment — bought in. Cash-strapped clubs across the league agreed, in principle, to loan a few of their American players to the new franchise.

"I was very skeptical of the whole idea," Lifton recalls. "Eventually I came to think that it might make sense because of the structure that Howard Samuels had set up in the NASL — of culling the best American players and then having the team be the American team in training for the World Cup as well as the Olympics. [I thought] that would be a way of attracting younger Americans who were increasingly playing soccer, certainly in high school and college."

Stadium Kick Game Program (courtesy of Alan Merrick)

Naturally, Team America would be based in Washington, D.C., a town accustomed to seeing soccer teams pack their things and go. The Whips, Darts and two different incarnations of the Washington Diplomats had already come and gone in the 15 years prior. "That has to hurt," Team America general manager Beau Rogers told Doug Cress of the Washington Post in January 1983, "but the Team America concept will erase all of those memories."

Lifton banked on his connections, working with NASCAR mogul Mike Curb — then treasurer of the Republican Party — to work out what was, at the time, among the largest sponsorship deals ever assembled for a soccer team in the U.S., an arrangement with Winston Cigarettes to the tune of a little more than $1,000,000.

With financing secured and the ink dry on an eight-year lease at RFK stadium, the USSF set about selecting Team America's head coach. Their short list included NASL fixtures such as former Dips and Cosmos head coach Gordon Bradley and Tampa Bay Rowdies head coach Eddie Firmani. But Fricker and the federation were thinking bigger. They wanted Dutch legend Rinus Michels, the former Ajax and Barcelona helmsman whose "total football" blueprint lives on to this day. But Michels — who'd spent a pair of seasons coaching the Los Angeles Aztecs in 1979-80 — said no.

"They asked [Michels] how long it would take for an American to become a good soccer player," remembers forward Tony Crescitelli. "And his reply was, 'Five years – that's how long it takes for a foreigner to become an American citizen.' So yeah, everyone was like, 'What the hell did he just say? Are you kidding me?'"

The USSF settled on a lesser-known name: Alketas "Alkis" Panagoulias, a naturalized American citizen.

Panagoulias made his name coaching the famed New York Greek Americans to a trio of U.S. Open Cup titles in the late '60s and guiding Greece to a Euro berth in 1980, their first ever. His first proclamation to the media as Team America's head coach was optimistic, perhaps naively so: "I believe the United States is, right now, a sleeping giant in international soccer. We will soon achieve a stronger position in the soccer world."

Panagoulias' statement came before he had a single player on his roster. Simply assembling those players would turn out to be a huge challenge, the first of many.

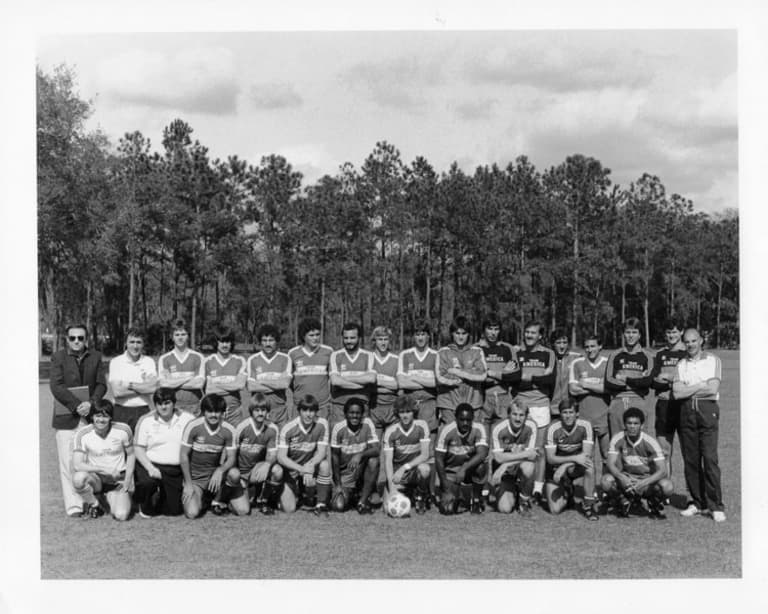

Team America (courtesy of Alan Merrick)

In February 1983, Panagoulias called 39 players from the first-division NASL, second-division American Soccer League and Major Indoor Soccer League in for a tryout in Tampa Bay. Many answered the call. Others did not. Not everybody was on board with the concept.

In Seattle, the Sounders had worked hard to build their own core of young American talent, and the trio of Benny Dargle, Jeff Stock and Mark Peterson had stayed behind (Peterson would later join Team America when it became clear Seattle would fold at year's end.) Elsewhere, Winston DuBose, Jimmy McCallister, Juli Veee — all potential contributors, chose to remain with their current clubs rather than chance it with Team America. A few days into camp, Cosmos striker Steve Moyers packed his things and left.

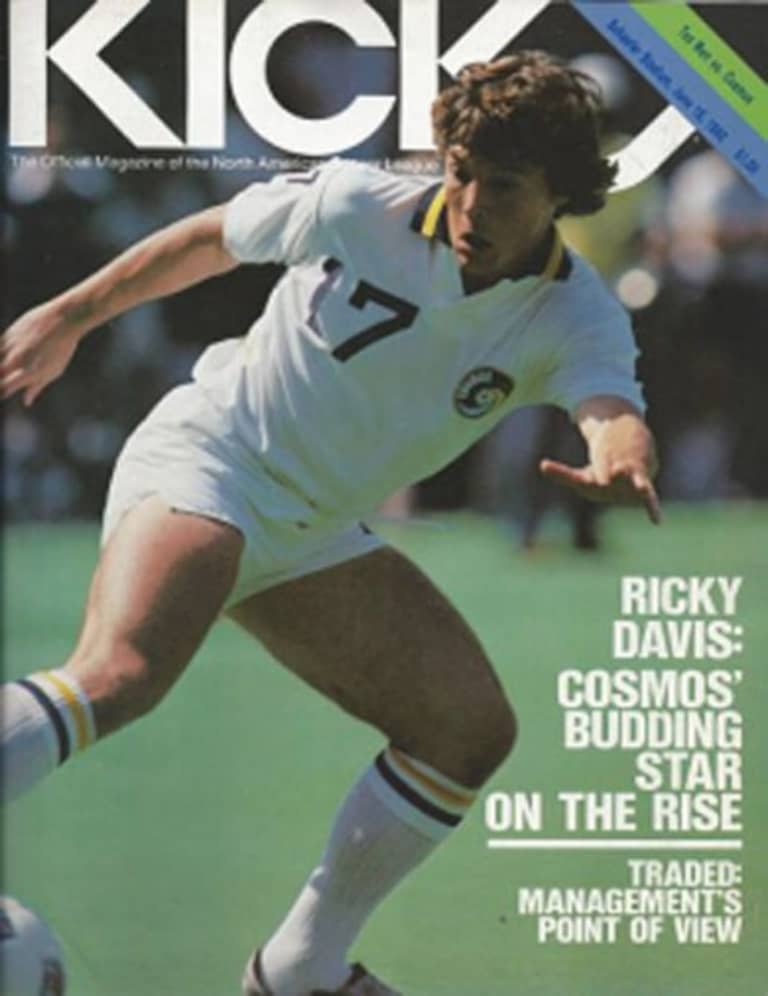

But it was Moyers' teammate, midfielder Ricky Davis — arguably the best American attacking player of his time — whose no-show made the biggest waves.

Ricky Davis

"The idea made a ton of sense," Davis told MLSsoccer.com. "We heard about the success that the US Olympic volleyball team had by becoming basically a 'team in training' year-round. So there were other examples in hockey and some other sports that demonstrated how that could work.

"Well, then the reality of what was really going on started to surface. It wasn't going to be all [American-born] players. It was going to be a mixture of American and North American and foreign players. There were a number of players that were being talked about or already included in the team – and I'm thinking, 'Hold on a minute. Are we really doing something to help the American player, or are we doing something to help the league add another franchise or team and one that they can hang the banner of red, white and blue on?'"

"As a kid, I had this dream [of playing pro soccer], and all of the sudden I'm sitting in a locker room with Pelé, Franz Beckenbauer, Giorgio Chinaglia, Johan Neeskens, Carlos Alberto," Davis adds, "all of these players that I, as a kid, had to struggle to go watch on closed-circuit broadcasts, but got to see them playing in World Cups. Now, I'm on the same team with them. So I felt that, at some level, my departure from the Cosmos would be a betrayal."

To a certain extent, Davis had a point. Alan Green – a Brit who was still working toward gaining his US citizenship – had joined up. On a green card, South African-born Andrew Parkinson had also been called into duty.

The players' union had sent Lifton a letter of protest, objecting to his use of non-US citizens. "What can we do?" Lifton told the Washington Post at the time. "We don't have any other Americans who can play." Both Green and Parkinson had declared their intention to become citizens. "I want to be an American; I want to play for Team America," implored Green.

Parkinson was similarly exasperated. With his birth country banned from international play, the US became his only chance at an international career.

(courtesy of Scott Ross)

Both would eventually become citizens. Both would play for Team America –Parkinson leading the team in goals – and eventually, both would receive a US national team cap.

For Davis, leaving New York – the only team in the league, at that point, with any semblance of stability – was an undeniable risk. But the writing on the wall at Giants Stadium was the same as it was anywhere else: the NASL was on life support. It might not survive another year.

"Instead of waiting for the wave to wash over us," Cosmos defender Jeff Durgan, Davis' teammate and friend, told Sports Illustrated at the time, "let's try to swim with it. I still have doubts, I still have fears. But I would rather be part of Team America and go under with them than with the Cosmos."

"Jeff Durgan," says Team America forward Tony Crescitelli, "he had balls. Do you know how much money [the Cosmos players] made, touring? [Jeff] believed in the Team America concept. I believed in it. I thought it was the most brilliant idea."

At just 21, Durgan had already spent three years in New York, honing his craft alongside Brazilian legend Carlos Alberto and emerging as a premiere American defender. It didn't take long for him to emerge as Team America's leader. Quickly after, he was named captain.

"He was one of the best center backs in the league, period," says Team America teammate Alan Merrick, reached by MLSsoccer.com earlier this year. "Forget nationality, he was one of the best players out there. He was as good as [Serbian defender Nemanja] Vidić. … I could wind Jeff up to kick his own grandmother, and he'd do it."

Others joined him. On the backline, Dan Canter came from Ft. Lauderdale and Rudy Glenn from Chicago. From Tampa Bay, midfielder Perry Van der Beck, the first player in US soccer history to be drafted straight out of high school and "the American Frank Lampard – work rate, incredible," according to Merrick.

Team America in Florida (courtesy of Alan Merrick)

Crescetelli arrived from the San Jose Earthquakes. "He was blistering. He was like a Michael Owen, from Liverpool. There were times when he couldn't trap a bag of cement. But then there'd be other times where he'd be so silky smooth that you'd go, 'Giorgio Chinaglia, eat your heart out.'"

Baltimore native Sonny Askew joined up – "basically just a teenager," Merrick says, "but he was another unbelievable raw talent." Askew remembers others. "Ringo Cantillo, he could play. Chico Borja, Boris Bandov. We had some players."

Still, with their season rapidly approaching, things looked grim. Davis wasn't the only player hesitant to come. Just three days before their regular season opener against Seattle, Team America had 12 players available. Two were goalkeepers.

"Right now we look like the 300 Spartans against the Persians," Panagoulias told the New York Times. "But I have faith in these boys."

Perry Van der Beck (7) vs. Fort Lauderdale Strikers (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

As it turned out, Panagoulias, who passed away in 2012, was more concerned with faith than tactics.

"He got hired by the federation," Merrick says, "but he was a token offer. I loved Alkis as a person, and as a man, but his coaching acumen was lacking."

What Panagoulias lacked at the blackboard, he made up for in gusto. And, for a while, that panache carried Team America toward the promised land.

"Alkis [was] a very emotionally driven man," Durgan told MLSsoccer.com. "I think he was a student of the game. I think he was an intelligent soccer mind. But relative to other coaching experiences I've had, Alkis tended to rely more on his emotional belief in the American athlete. … He just believed there was this underlying American spirit that would carry us through.

Alketas "Alkis" Panagoulias (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

"The credit I would give [Alkis] is that he probably believed in us and our abilities more than any of us did. And especially early on, he really sent us out onto that field with a sense that we really could take on people and be competitive."

Buoyed by that enthusiasm, Team America managed to surprise cynical observers early in the 1983 season. In their inaugural match at the Kingdome, they battled to a shootout victory over the Sounders.

The match was a defensive struggle, something that would become a trademark of the team. Although other teams had finally warmed to the idea of releasing some of their players, some like Davis still remained behind, leaving Team America a bit punchless. Still, Durgan and the backline held steadfast.

The press were nonplussed. "The game seemed more like an exercise in futility than a display of American soccer prowess," read a story in the Washington Post the following day. Unbothered, Team America pressed on, besting the Tulsa Roughnecks before suffering a shootout loss to Seattle at RFK Stadium.

Relative success had come earlier than expected, but Panagoulias' rag-tag bunch had their work cut out for them. The next day, while the team was preparing to depart for Jamaica to play a friendly against Watford, Team America's head coach watched his players straggle in after a night on the town.

"We're all waiting for the bus to take us to the airport," Van Der Beck remembers. "And just to see each player get out of their car, just dressed differently; Rudy Glenn gets out of the car and has these tight leather pants on and a tight vest – it's studded. He's got sunglasses on and a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. Next guy gets out, and it's Greg Villa. He's massive. He's wearing these tiny shorts, a muscle shirt and flip flops.

"Alkis is looking at these guys, just thinking, 'What the [expletive]? This is a [expletive] national team?' It was just crazy."

But, for a time, it worked.

Team America celebrates (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

"The chemistry of the players was great," Merrick says. "We gelled together as a team, as units on and off the field. We had good characters on the team, so I think that, in the early stages of the season, some of the teams underestimated us. Early on, we capitalized on that big time."

Victories against Tulsa, Tampa Bay, Fort Lauderdale followed. A win against the Cosmos – the New York Cosmos – barely imaginable at the onset of the season, became reality just a third of the way through it. In perhaps the most surreal moment of the entire campaign, Franz Beckenbauer – Der Kaiser – chipped his own goalkeeper, handing Team America a 2-1 win and first place in the Southern Division standings.

And, of course, Ricky Davis was there to see it. Durgan wasn't supposed to be – he'd picked up a red card a week earlier – but the league office had overturned it, perhaps eager to see the two former teammates clash.

Several games later, in a re-match at Giants Stadium, Davis seemed to have a target on his back. "We gave him some grief, up close and personal and also on the field whenever we saw him," Merrick says. "There were some lighthearted jabs, and there were some others that were certainly a lot more direct, where we made sure he knew he was letting us down."

"[The backlash] did have an effect on me emotionally," Davis says. "It bothered me. It cost me a number of really good friendships, in particular my friendship with Jeff Durgan."

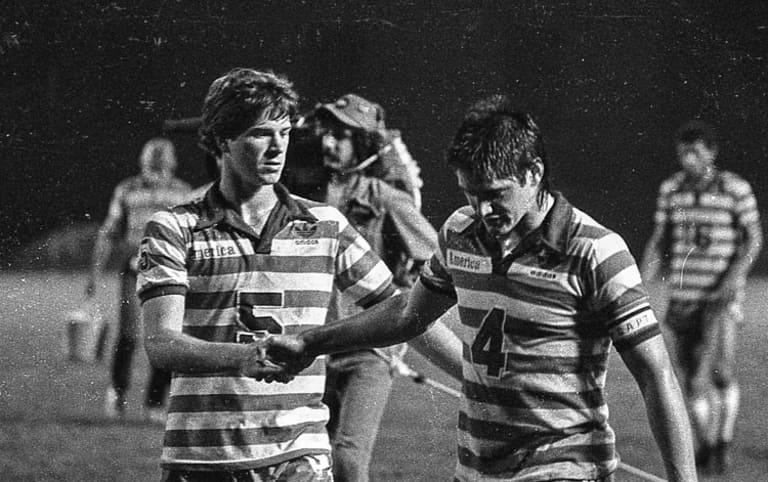

Late in the match, Davis collected the ball near midfield and cut a path toward Team America's penalty area; Durgan careened into his former teammate from behind. Yellow card. It could have been red. It seemed personal. To Durgan, it was all business.

"I was an equal opportunity hitter," he remembers. "… Where the opportunity and the threat is, that's what I would attack. I don't recall necessarily hitting Ricky in any of those games. If I did, it's because he was in a place where he needed to get hit."

Video courtesy of Dave Wasser

It wasn't the first time Durgan had left his mark on an opponent. After a particularly rough 1-0 victory over Tampa Bay in June, Rowdies forward Tatu went after Durgan: "He was like an animal…. I was afraid for my life," the Brazilian told the Post. After a similarly scrappy outing a month earlier, San Diego Sockers president Jack Haley said Durgan was "just another hatchet man for those butchers" before labeling the entire squad "Team Animal," a moniker that would stick throughout the balance of their debut campaign.

It had been a good run for Team America, but cracks were starting to show. Panagoulias' reliance on American spirit bought some time, but it could only take the team so far. Training sessions had become hour-long sessions of throw, head, catch. "Alkis would just sit down, curse at us and smoke cigarettes," remembers Crescitelli. "Actually [defender] Alan Merrick was running most of the trainings. [Alkis] didn't have a clue. Alan was basically doing everything."

Merrick took note of Panagoulias' shortcomings then took the opportunity to share some of his veteran wisdom with his teammates. "I'd get the guys together, and go, 'We need some fitness, we need to do some set plays, and we need to do some structured stuff,'" Merrick says. "So yeah, I did a lot of practices. And in the end, [Alkis] called me to one side and said, 'Stop undermining me.'"

Other players faced their own issues. Askew found himself benched midway through the year; the hard-nosed Baltimore kid had trouble adjusting to Panagoulias' way of running things. After a loss to Tampa, Askew had had enough.

"I called Linda, my wife, from Tampa and I said, 'I'm done.'," remembers Askew. "So we land [in DC], and we're gonna play Juventus at RFK.… [Alkis] comes up to me and says, 'You're gonna mark Marco Tardelli. [The Italian legend who scored the game-winner in the 1982 World Cup final.]'

"And you gotta understand, I'm about to tell him that I'm done. I said, '[Expletive] Tardelli, he's gonna mark me.' And Alkis loved that. I'm telling you, I think I started the next 11 games after that comment. He grabbed me by the shoulders, shook me, said, 'I love you, I want you to play – I need that out of you on the field.'"

"Sometimes you can get people wrong," Askew adds. "He loved us."

Jeff Durgan sent off (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

But D.C. didn't necessarily love Team America. Attendance started to dwindle after peaking following a near sold-out crowd of 31,112 against the Cosmos in early June. Certainly, some had come to see the home team. Others had come to see Chinaglia and Beckenbauer. During a sold-out game against Ft. Lauderdale later in the summer, most of the 50,108 in attendance came to see the Beach Boys, who performed after the match.

The team finished the 1983 season averaging barely more than 13,000 fans a game – a respectable number, but one grossly skewed by the Beach Boys-inspired sellout, which comprised a quarter of Team America's total attendance.

"The lack of scorers, the lack of excitement, the lack of press coverage of any real substance – it all resulted in no great local support for the team," Lifton says. "For example, at RFK, I had some representatives from Winston down for a game and nobody was paying attention, because nothing was happening. Of course that's endemic in soccer – we know that. You have to be excited by the build-up and the attempts rather than the scores, but the team we had wasn't even getting that many attempts. It was always a defensive game."

"It was the worst year, ever, in my career," says Crescitelli. "I couldn't score a goal to save my life; it was horrible. I was doing well in practice, but once it came to the game, I was horrendous. And I blame myself. It all fell apart, and I take plenty of the blame, because I couldn't hit the side of a barn."

Injuries, too, piled up. The reluctance of Davis and others to join the club left Team America with a paper-thin bench.

In a strange twist of fate, Team America drew another team down in its wake. The Canadian Soccer Federation had taken a shine to the team-in-training model and launched their own ultimately unsuccessful bid to host the '86 World Cup. Before the start of the '83 season, the CSA announced they were partnering with Molson to convert the Montreal Manic to "Team Canada" in 1984.

The concept alienated many fans of the Manic who'd grown accustomed to the Manic's high-octane, attacking brand of soccer and couldn't be bothered to support a team that would largely be re-shaped at the end of the season. The club went from drawing over 20,000 fans a game to averaging 9,910 in 1983. They'd fold at year's end.

"There were times we had 14 players in-house," remembers Durgan. "The Cosmos had 30 in-house." It all became too much to bear.

Reeling, Team America spun into the abyss. They dropped 13 of their last 15 games, plummeted to the bottom of the Southern division and finished dead last in the league.

After their final loss of the year – a home defeat to Ft. Lauderdale in front of fewer than 5,000 fans – Lifton, who had long been running in the red, turned the lights off on Team America. He had long since expressed his frustrations with the U.S. Soccer Federation, who had promised, and failed, to schedule international friendlies at year's end and deliver on hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of marketing. Lifton himself had lost some $750,000 in 10 months.

"They wouldn't even let us take the jerseys," Askew recalls. "They came around with a garbage bag and said, 'Hey, you gotta turn in your stuff.' I was just like, 'Keep it. I wish you well.'"

The league itself would go under a year later. But not before the NASL attempted to draw Lifton in one last time.

"They offered me the opportunity at the end of the '83 season to buy [the Cosmos,]" Lifton says. "I think that was even more telling in its own way than what happened to Team America; they were coming to me to buy the Cosmos because they figured that I was, to use the phrase, 'a schmuck with a fountain pen.'"

Team America verus New York Cosmos (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

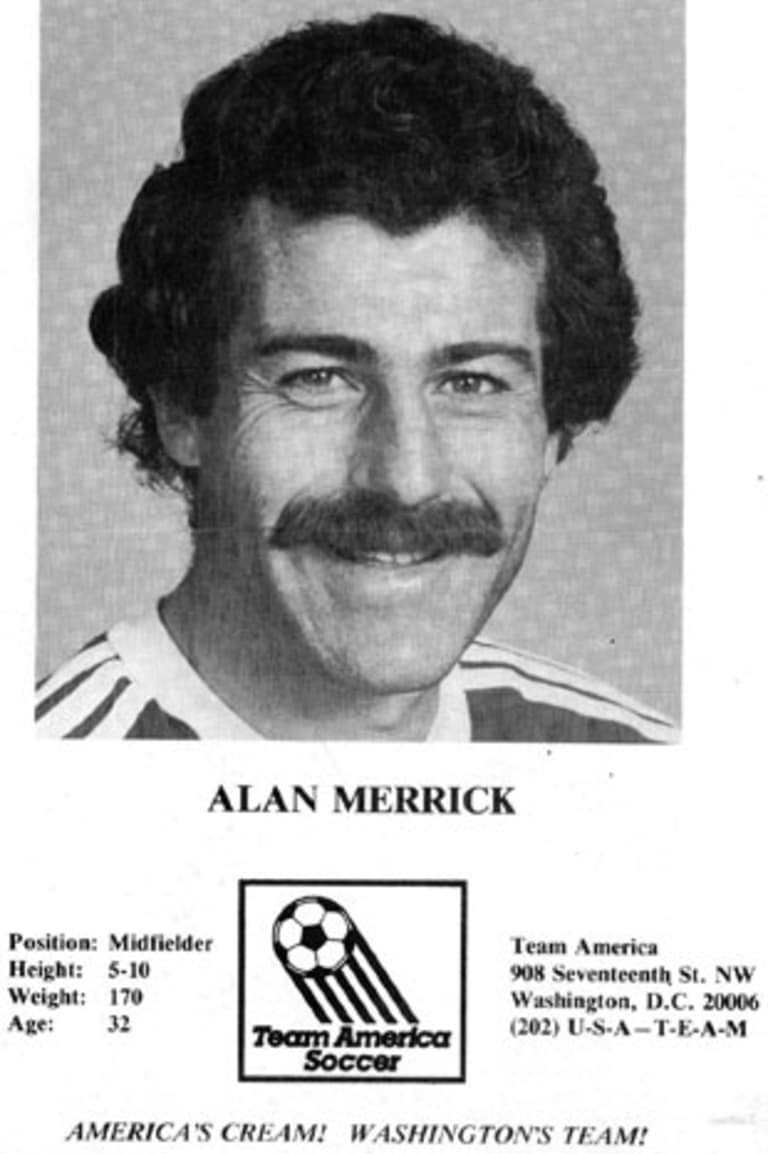

Alan Merrick somehow managed to keep his Team America kit. "This last Fourth of July, I actually wore my Team America shirt and I could still get it on," he says, chuckling. "I challenge all the other players to get theirs on."

He also remembers his first and only US national team appearance quite fondly. It came, of course, during his time with Team America, a 2-0 victory over Haiti in Port-Au-Prince in April 1983, the only match the US played that year, with 12 of 14 players and both goalscorers – Jeff Durgan and Chico Borja – hailing from Team America. Emotion wells in Merrick's voice when he describes descending from the hills toward Haiti's national stadium.

"Having my hand across my chest and singing the national anthem was a very poignant stage in my career of playing the game," he says. "I was very proud to be an American."

He did not anticipate that it would be his only appearance in a US jersey. Merrick, like many other Team America players, had sacrificed much for the concept, moving his family from Minnesota to D.C. in anticipation of taking part in qualification for the 1986 World Cup. Like many of his teammates, Merrick places much of the blame for Team America's failure on a lack of support from the U.S. Soccer Federation.

Alan Merrick in 1983 (courtesy of Alan Merrick)

"We didn't feel as if they were supporting us at all," Merrick says. "We were just out there. It was almost like they did their washing, they put us out there on the line soaking wet and then just said, 'OK, we'll take all the wind out of their sails, we won't even breathe on them and see if they dry.' We never saw anybody from the federation."

"They hung up their laundry and left the state," echoes Durgan.

"The retroactive thinking of the USSF … it was impossible to move them," Lifton recalls. "I think the people who were running [the federation] were old soccer players. They were not the hotshot technologists of tomorrow; they were the old guys of yesterday. They didn't know much about marketing, they didn't know much about the press and the like."

Team America folded, but Panagoulias held on to his job. His nightmare was just beginning. Panagoulias was about to guide U.S. Soccer into perhaps its darkest hour, a qualifying campaign that would culminate with a memorable, calamitous crash-out against Costa Rica in Torrance, California.

Though some on Team America's roster figured into Alkis' qualifying plans – Van der Beck, Canter, Arnie Mausser and, for a while, Durgan, to name a few – most did not, a development that felt like a knife in the back to many who'd left the relative comfort of their respective NASL clubs for the uncertainty of Team America.

"I was kind of upset that – when the team finally did start playing internationally – they started calling guys like Ricky Davis in, instead of calling the guys who had literally given up their former teams to come to Team America," says Crescitelli.

"Of course there was a sense of betrayal. I blame Panagoulias for that. I may have not played well, but I gave up my starting spot with San Jose to come join your team. At least show some little bit of loyalty and respect."

"They didn't go back to some of the players that played for TA, they went elsewhere – they went to the college ranks, they went into areas where their knowledge was still in its infancy," adds Merrick. "I was amazed at some of the appointments that were made. I'm going, "Oh my God, they are just putting the game backwards at this point."

Dan Canter (4) shakes hands with Jeff Durgan (5) (courtesy of Tony Quinn)

Seven years later in 1990, under the guidance of head coach Bob Gansler, the US, after a 40-year wait, qualified for the World Cup. They haven't missed one since.

In 1994, with the world watching, Lalas, Balboa, Wynalda and rest of the '94s – a "team-in-training" from Mission Viejo – got soccer in the United States off life support, this time perhaps for good. It's enough to make several of Team America's members wonder if their concept, widely panned at the time, was just a bit ahead of its time.

"I thought it was incredibly innovative," says Merrick, who went on to coach the Minnesota Strikers in the NASL and MISL, and has since landed back in the Twin Cities as a youth coach. "It was one way that clear-minded people were thinking – if we can project our national team across the world, the game will obviously get to a higher level in the United States.

"[They should've kept it] running for a longer period of time. It was one of those things where you thought, 'Don't throw us out with the bathwater here.' And that's just what they did."

Video footage courtesy of Dave Wasser