CARSON, Calif. – Danilo Acosta worked four long years to bring his son from Honduras to Salt Lake City, and when things finally fell into place – the paperwork complete, the documents signed and stamped, the flight from Tegucigalpa rolling up to the gate – he knew what little Danilo, just 12 years old, needed to see first.

“The first thing I did was take him to Rio Tinto Stadium,” says Danilo, the father, who had left his native country before his son's birth and settled in Sandy, Utah. “We got here about 1:30 in the morning, and I told him we were going to come here and watch games. … I took him to Rio Tinto, and he said, 'I want to play here.'”

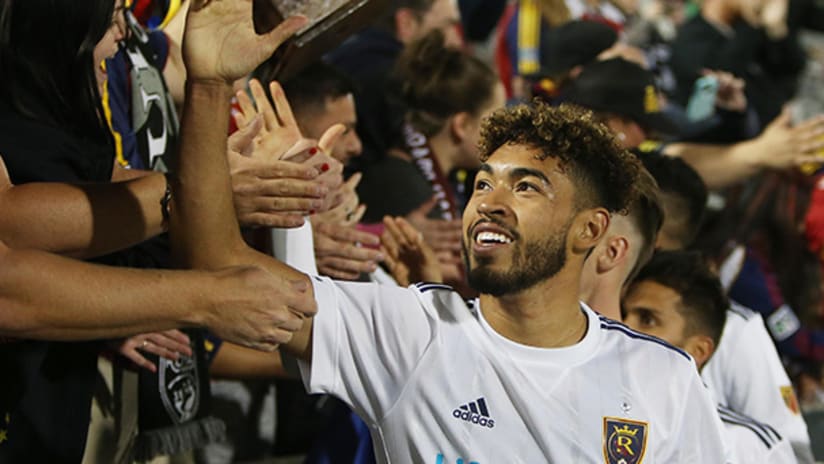

Eight years later, 20-year-old Danny Acosta is Real Salt Lake's starting left back, a rising phenom who played a key role ftor the US Under-20s last year as they won their first regional title and reached the U-20 World Cup quarterfinals. He’s now one of the youngsters US Soccer is looking to as it builds for the future after the national team’s failure to qualify for the World Cup, earning his first senior USMNT call-up for the recently completed January camp.

He's living the American dream, in a big way, and for his dad, that validates all the sacrifice, all those difficult years apart.

“He's accomplishing what he wanted to do …,” Danilo told MLSsoccer.com. “At the end of the day, that's what American culture is about. If you work hard, you can achieve anything.”

Danny Acosta during his academy days. | Real Salt Lake

Danny, who had never played organized soccer before coming to Utah, joined RSL's Arizona-based academy at 15 and excelled on their youth teams before signing a Homegrown contract in December 2015. He made his first-team debut last August and featured in 17 league matches, 16 as a starter, as RSL made a late run under Mike Petke that has many optimistic about the club headed into this season.

He fought off long odds to get here. Well before Danny Acosta began climbing the ranks at RSL, before Tab Ramos plucked him for the US U-20s, before he was invited to January camp, before everything started falling into place, he was just another soccer-loving kid playing all day on the streets of San Pedro Sula, considered for a time the most dangerous city on the globe.

He saw things he's not sure he should talk about, the kind of things no one should ever have to witness. They were but everyday occurrences in San Pedro Sula.

“San Pedro Sula is really violent,” Danny says. “It depends where you go. Some areas are really nice, but I wouldn't go. Because of the way it is right now. I was going to go back in December for Christmas, spend time with the family, but they told me not to come, because they have no president [that has been accepted following fraud claims in last November's election], they closed all the stores, people started robbing [the stores], and they were getting killed and all that. … I don't know what's going on, to be honest.”

It's considered far safer now than when Danny was growing up. His father was in the US by the time he was born, and his mother was out of the picture soon after. He was raised by his paternal grandparents in San Pedro Sula's Barrio Cabañas neighborhood.

“I was basically playing soccer ever since I could kick a ball,” Danny says. “It's always been in my blood. My dad played, my uncles, and it's always been around me.”

He played with his friends, and sometimes the kids in the neighborhood would form a team and face off against other neighborhoods. “Whoever wins,” he says, “they get, like, sometimes money, or sometimes [the loser] would buy the drinks, like sodas and all that.”

It was a mostly blissful childhood, but Danny knew that darker forces reigned in his city.

“When I was 8 or 10 years old, yeah, we knew [the city was dangerous],” he says. “Where we were at, everyone knew each other, so there was nothing violent, but outside of where everyone [we knew] was, you couldn't go. There were certain parts [of San Pedro Sula] you would not go, because you didn't know the people and you didn't know what was going on. So if you start something, you probably end up getting killed, getting shot, or something.

“But in the neighborhood I was living in, everyone knew each other. They knew my family before I was born. It was basically like a family in the neighborhood.”

Things turned bad across the city starting in the early 2000s. Drug trafficking, gang wars, land disputes, the rise of organized crime, police corruption and political upheaval and a 2009 coup led to a rise in violence across the country. In San Pedro Sula, Honduras' second-largest city – and the venue for Honduras' national team matches – things were at their worst.

“San Pedro Sula was a nice city … but things got bad,” Danilo says. “Things really got worse when Danny was around 4 or 5, All these gang members, friends getting killed, people getting killed. [The family] lived in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the city.”

By the early 2010s, shortly after Danny departed, the homicide rate topped 170 per 100,000 residents, putting San Pedro Sula above Acapulco and Caracas as the world's most dangerous city. And if things seemed nice in Barrio Cabañas, trouble wasn't far away.

Danny has vivid memories of things he wish he'd never seen.

“There's some stuff that I don't know if I could tell you,” he says. “There's some stuff when I was playing soccer as a little kid. Once there was a guy like [100 yards] away. We're just playing soccer, and the next thing you know, this guy is on a bike, and a car [chases him] and they get out [of the car] and just start shooting him.

“That will blow your mind. Especially being a little kid.”

Danny Acosta takes on RSL teammate Brooks Lennon at USMNT camp. | Robert Mora

Danilo had left for the US in 1997 to “pursue a better life,” and the plan was that he'd bring Danny and Danny's mother north as quickly as possible.

“The idea was that I was going to work and save money and bring them here illegally,” Danilo says. “We were going to pay someone to bring them to the United States, to the border. But things didn't work out. And we didn't bring Danny here until he was 11 years old.”

Danny's mom was gone soon after his birth, and Danilo's parents – Danny calls his grandparents “mom” and “dad” – stepped in. Danilo did all he could to keep contact with his son.

“It was hard,” Danilo says. “I used to call every day just to make sure he could hear my voice. Danny, since he was a little kid, all he wanted to do was kick a ball. I used to call in the afternoon, 'Where's Danny?' 'Oh, he's out there playing in the street.' I'd call him for a minute, and he'd say, 'Pop, I got to go back and play.'”

Danilo married in Utah, and he and his wife, Claudia, had another son, Israel, who is now 17. Danny was 8 when Danilo received his residency papers, enabling him to return to Honduras. They met for the first time at the airport.

“Danny was standing right there, and he's just looking at me,” Danilo says. “I called him, I said, 'Come here,' and he just ran to me and started crying.”

Danilo began the process for his son to legally immigrate, but there were problems with Danny's documentation, and it took another four years before approval was granted. He arrived in Sandy, where the family home was walking distance from Rio Tinto, knowing nearly no English. He'd practice at home, read the subtitles while watching TV with closed-captioning, and used a Spanish/English dictionary at school.

“I learned pretty quick,” he says. “I'm still learning a few words, and I still got the accent. Little by little I'm losing it, but I'm starting to forget Spanish, that's the thing. When I talk to my grandparents in Honduras, I'll be talking in Spanish, and then I'll forget a word, so I say it in English, and they'll say, 'Did you forget Spanish?'”

Danilo, as promised, took Danny to Rio Tinto to see RSL play, and he met former center back Jamison Olave, who offered encouragement. Danny started playing club soccer, moving to better and better teams, and his father provided individual instruction, molding him into a holding midfielder. Danny wasn't the most talented player – he readily admits so – but he wanted it more and put in the work.

“He's got that street-soccer mentality that we grew up with in our country,” Danilo says. “That desire. Doesn't want to lose. The desire that if you do lose, you've got to go back out there and be ready for the next opportunity. He wasn't the best player, but I think he's got a bigger heart than anybody else, to be honest with you.”

Danny didn't make it the first time he tried out for RSL's academy, but he worked hard to shore up his shortcomings and impressed the staff a year later. He was off to Casa Grande, Arizona, some 540 miles to the south. That was difficult for his family.

“Can you imagine?” Danilo says. “I get him over here at 12, and he left when he was 15. We had only been with him for two and half years. It was very hard for all of us. Yeah, he's in the United States, but I couldn't see my kid. But it's what he wanted to do. I asked him before he was going to leave, 'Are you sure about this?'”

Danny was sure. He quickly embraced the routine – school, training, study hall and meals – and grew close to teammates, a group that included several players now with RSL's first team: Justen Glad, Brooks Lennon, Sebastian Saucedo, Aaron Herrera, Jose Hernandez and Corey Baird.

“Those guys you play with, go to school with, they become your teammates, but more than teammates, they become your family,” Danny says. “You see them every day and you care for each other.”

His game got stronger, and as he watched teammates go off to US youth national teams – and come back with “free gear, cleats and running shoes; I would love to have that, too, like any other kid” – he found new motivation. Danny was called into the U-18 national team, where Javier Perez converted him to center back, and Ramos brought him into the U-20s soon after. When RSL moved him to left back, Ramos, too, moved him wide.

Danny and Danilo became American citizens about a year ago – Ramos and RSL both helped to get it done – just in time for Danny to play in the CONCACAF U-20 Championship. He was Ramos' left back in all but one match as the US overcame an opening-game loss to Panama to qualify for the World Cup and reach the title game. The Yanks' opponent? Honduras.

Danny was excited to go up against his native country. So was Danilo, who was tracked down the day before the game by a Honduran newspaper. He told the reporter that the US had “given us everything,” had “opened the door for us” and given his son “the opportunity to succeed and realize his dream.”

“He's going to do what he's got to do,” Danilo said. “He's defending the colors of [the United States], and that's got to be in his heart first.”

Danny went the full 120 minutes in a scoreless draw. Penalty kicks would determine the champion, and Ramos asked him if he wanted to take the third American attempt. Danny said he'd rather go fifth. His teammates joked that he better not sell them out now.

The first seven shooters – four Americans and three Hondurans – scored, and then Rembrandt Flores missed on Los Catrachos' fourth attempt. If Danny converted, the US would win its first CONCACAF U-20 title.

“I was nervous until I saw [Flores] miss, and then I was like, 'Wow, OK, here we go,'” he says. “I just put the ball on the spot and then took the shot and lucky it went in.”

He didn't openly celebrate when the ball hit the net – “to respect Honduras and my family” – but joined in the fête when his teammates surrounded him. “They're my brothers,” he says. “Of course, you've got to celebrate with them. I'll have that for the rest of my life.”

Danny made his RSL debut a month later, in early April, going the full 90 in a 3-0 romp over Vancouver at Rio Tinto. He was the first-choice left back the rest of the season, starting all but five games the rest of the way, not counting the eight he missed while in South Korea for the U-20 World Cup.

Playing at Rio Tinto was all he'd hoped it would be. But it was just a start, nothing more.

“That dream I had been working on for two and a half years [since arriving in Utah] – for all my life, you could say – and once I got there, it was something special,” he says. “But you've got to go back to work, you know what I'm saying? Yeah, you can live in the moment a little bit, but you can't live there too much, because the next day it's back to work and prepare for the next game.”

The invitation to the annual January camp provided more validation. Danny spent nearly three weeks with interim US coach Dave Sarachan and his staff, and although he didn't make the roster for the scoreless draw against Bosnia and Herzegovina that closed camp, that's not a setback. The message? Work harder.

“[Being in camp] means everything to me,” he says. “Whatever I did last season has paid off so far, and just being around here, in this environment playing against some of the best guys in MLS, and I'm learning from them. Coach told me just keep doing what you're doing and someday you'll be up there [as a national team regular].

“That motivates me more to be here, to work even harder.”

He can envision what it will be like to play for the US, to play in games that mean something. To play in a World Cup.

“I can imagine, but I don't want to imagine,” Danny says. “I want to be there. That's the goal, to be there. Imagine is one thing, but being there is a whole other thing.”

Danilo can imagine it, too, and thinks his son’s American dream will soon be fully realized.

“I think it will be the American dream come true,” he says. “When Danny wins the World Cup with the US, I think within 10 years, you will see that.”