As it gets set to open its 25th season, today's Major League Soccer is a vibrant league, soon to number 30 clubs. But when it launched in 1996 it was a novelty: a fledgling soccer league with 10 charter teams that carried the weight of proving that professional soccer could thrive in the USA, and subsequently Canada.

In a nod to those supporters who helped lay the foundation of the league back in those early days when the future was far from certain, MLSsoccer.com tracked down 10 who have held season tickets since the launch of their clubs.

Taken together, their stories showcase just how much their existence became interwoven with that of their MLS club's: life-changing events would be forever attached to specific MLS matches, players or moments. Through their fandom, many of the fans solidified family bonds and some formed new ones, giving rise to a whole new generation of fans (in some cases two generations) who experience the elation—and mostly despair, in the case of some clubs—of supporting a soccer team in the United States.

Through decades of change, however, the overarching theme here is commitment. Each of the fans profiled below was asked about wavering on their season tickets at some point since the 1990s, and only a few admitted they’d briefly considered it. What keeps them coming back, they often said, was exactly what keeps any community together for 25 years—an appreciation for those around them, and a sense of belonging.

Said one fan: “Being a fan of this team is part of the identity you carry on your sleeve. It’s part of who you are.”

"Don't bring other soccer jerseys into my classroom"

The second-grade students in Carlisa Perdomo’s classroom abide by a number of rules throughout the course of the school day, but not many loom larger than a unique dress code put forth by their teacher.

Perdomo has spent the past 24 years as a teacher in Southern California and just as long in the embrace of the Galaxians, a fiercely committed supporters group for the LA Galaxy. The Galaxians serenade players with songs in English and in Spanish, and boast the coveted title of the first supporters’ group in the club’s history, dating all the way back to 1996.

“The students already know, you don’t bring other soccer jerseys into my classroom. They know I’m hardcore,” says Perdomo, who currently serves as the president of the Galaxians.

Perdomo is the daughter of Salvadoran parents who emigrated to the Los Angeles area decades ago. The Galaxy piqued her interest while she was in her early 20s when she heard that the club’s first signing was famed Mexican goalkeeper Jorge Campos, and she quickly snatched up tickets to the club’s inaugural game at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.

It was there that she first connected with the Galaxians — “They were singing and banging drums, I just wanted to check them out,” she says — and she’s rarely missed a moment of the action since. She rattles off the names of her favorite players over the past 25 years with surprising ease — former goalkeeper Kevin Hartman tops her list — and she watched four of the Galaxy’s five MLS Cup wins in person.

Perdomo’s own kids were born with soccer in their blood … and their names. Her 20-year-old son Marcelo Alessandro shares a name with former U.S. national team and MLS star Marcelo Balboa and Juventus great Alessandro del Piero. Her daughter Mia Kristine, 15, bears the names of U.S. women’s national team heroes Mia Hamm and Kristine Lilly.

Her second-grade students know the game, too.

“Sometimes when they’re acting crazy I’ll use one of our cross-chants, and I’ll yell, ‘LA!’ And they yell right back, ‘Galaxy!’” Perdomo says. “Then I know I’ve got their attention.”

"It's an absolute act of faith to love an MLS team"

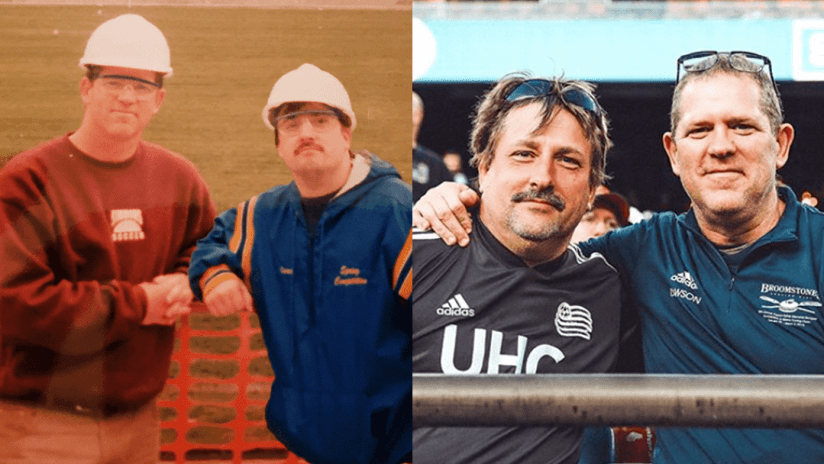

The way Dick Dawson views his 25-year relationship with the New England Revolution, he always had a choice to leave. He just never wanted to go.

Of course there were rough times in Foxboro over the years —five losses in the MLS Cup Final, Steve Ralston’s emotional final game, Preston Burpo’s broken right leg, two bottom-of-the-table finishes in 2011-2012— but Dawson, who was one of the first season-ticket holders in club history, never truly wavered.

“It’s an absolute act of faith to love an MLS team,” Dawson says. “Back in 1996, you weren’t born into it, your parents didn’t just tell you, ‘This is how we do things.’ You had to embrace the fact that there was a team right in front you, and it was yours to support.”

Dawson’s history with the Revs traces back to the days before they even formally existed. When word broke that New England had been granted an MLS club, he reached out to Joe Cummings, the Revs’ assistant GM in the early years and a fixture on the New England youth soccer scene. Dawson wanted to lock in tickets although there was no formal way to buy them.

“I told him I wanted to write him a check,” Dawson says. “He had nothing to give me in return because they didn’t have tickets printed yet, they didn’t really exist. But he took the check and I trusted him.”

So began Dawson’s two-plus decades of devotion to the Revs, littered with sweltering summer days and frigid November nights at the now-defunct Foxboro Stadium and Gillette Stadium’s Section 108. From his front row seat he’s cursed the team’s shortcomings or a wicked bounce off the turf, but all while embracing the club and its most devoted fans.

“I’ve had great times and some terrible times. I’ve raised a child on the Revs. People’s parents have died, kids were raised and gotten married,” Dawson says. “You’re part of a community, no matter what the team does. I can’t imagine going to a game and sitting somewhere else.”

"It helped us get through the rough time"

Of the roughly 1,500 names on the wall honoring founding members of the National Soccer Hall of Fame in Frisco, Tex., one set of parents witnessed just about every key moment en route to professional soccer taking root in Texas.

Frank and Cindy Sanders were there when the Dallas Tornado toiled in the North American Soccer League (NASL) in the 1970s and then when the Dallas Sidekicks played indoor soccer during the 1980s and 1990s. They were there when the Cotton Bowl hosted a handful of games during the FIFA World Cup in 1994.

And when MLS granted Dallas a club for its 1996 inaugural season, they were among the club’s first devotees, 20 rows up from the midfield line.

Their son, Bert Sanders, was there on opening day too, away from college for the weekend and happily sitting with his parents to witness history. Over the next 18 years the three attended countless games at the Cotton Bowl in Dallas and then Dragon Stadium in suburban Southlake before Frank, a civil rights investigator for the U.S. Department of Education and a certified youth soccer referee, passed away from cancer in 2004.

Bert and his mother dealt with the loss over time, and over soccer. The two kept the season tickets they’d had since 1996 and rarely missed a match after the team re-branded from the Dallas Burn to FC Dallas and moved to Toyota Stadium in Frisco in 2005.

“I think it helped both of us get through the rough time after my dad died,” Bert Sanders says. “I knew it was something my dad enjoyed doing with her and she still enjoyed going to the games. And I think it made us closer—we saw each other every week. She would even come to my house to watch the away games.”

Cindy Sanders passed away in February 2018 at the age of 69. But the FC Dallas tickets stayed in the family. And when the National Soccer Hall of Fame first erected the wall of founders before the 2019 season, the Sanders family were one of the first names etched into history.

“They loved the game, and that was my way of honoring them,” Bert Sanders says. “The fact that I’m still using the same tickets my parents used, that will always give me a connection back to them and what they did to support soccer in Dallas.”

"I spent every cent I had on those tickets"

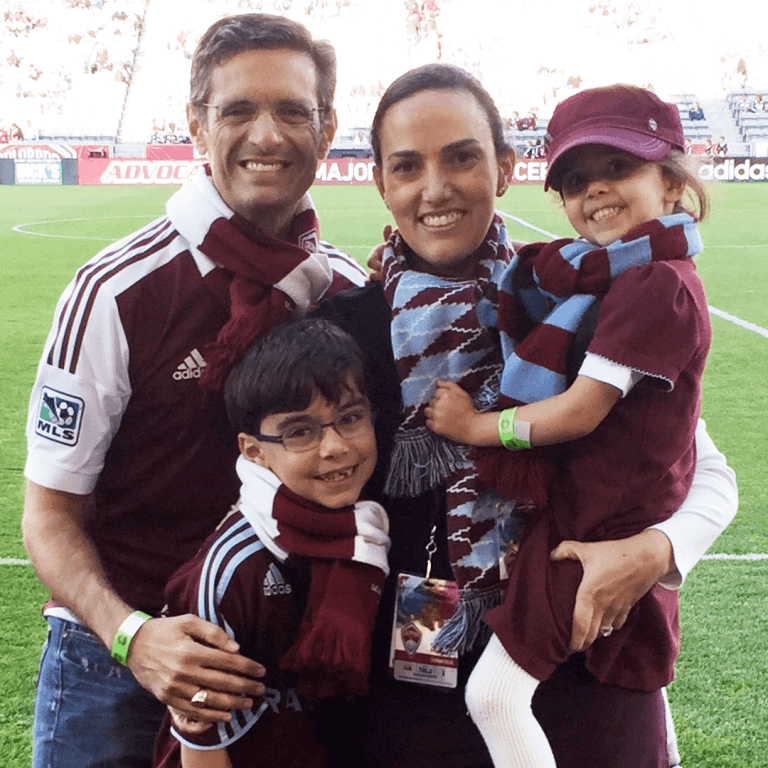

Andrew Fedorowicz was a medical student at the University of Colorado in early 1995 when MLS existed as a tangible but still somewhat nebulous promise to American soccer fans. The league was set to debut a year later but there was no indication which U.S. markets would land a team. So Fedorowicz spent his free time outside of grad school scouring online soccer chat rooms looking for clues.

A rabid soccer fan, Fedorowicz spent plenty of summer nights in the 1990s at games for the American Professional Soccer League’s Colorado Foxes, which averaged less than 6,000 fans a game.

When Denver was ultimately selected as an original MLS club, the details were murky in the beginning. During those early years of the internet Fedorowicz proved himself a capable sleuth who uncovered an address where it appeared the new Colorado franchise was setting up shop—555 17th St., a 40-story high-rise in downtown Denver—and he took a quick trip from Boulder to see if he could learn more.

“There were three people in a mostly empty room, moving boxes around,” Fedorowicz says with a laugh. “They didn’t have a system for processing ticket purchases or anything like that. They had paper forms where they had crossed out the name ‘Rapids,’ because that wasn’t even public information yet.”

Fedorowicz was undeterred by the club’s austere beginnings. He was a 24-year-old graduate student with an accordingly modest bank account, but he cut a check for $2,100 to cover the cost of two season tickets for the 1996 season and officially became the club’s first season ticket holder.

“I spent just about every cent I had for those tickets, but they needed people who were going to be supportive,” Fedorowicz says. “I’d gone to Foxes games where it felt like there were 50 people in the stands, and in my mind the MLS club had to be successful. And that required fans who wanted to spend the money and be part of the group.”

Fedorowicz has held season tickets ever since, moving from the now-defunct Mile High Stadium to Dick’s Sporting Goods Park in 2007 and moving his seats to where they are now, at a family table on the concourse at the top of Section 128. He held the Philip F. Anschutz Trophy after the Rapids won their only MLS Cup title in 2010, he and his wife Chrissy have raised two sons on the Rapids for more than a decade, and he insists he’s never flinched in his support for the club, or forgotten about his status as the club’s original fan.

“It’s a quiet point of pride for me, but most people have no idea I was the first season ticket holder,” Fedorowicz says. “I’m just happy to be one of the crowd.”

"This team is important to the entire family"

Margaret Kehoe and Robert O'Shaughnessy Jr. met on Feb. 4, 1966, set up on a blind date by mutual friends. She was a senior at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati and needed a date to a school dance, and he was a student and club college soccer player at the University of Notre Dame, roughly 245 miles away in South Bend, Indiana.

It took Kehoe six months before she realized that the man who drove four hours for that date was worth keeping, and by 1969 they were married and living happily in Columbus, Ohio. He eventually served as the fourth-generation owner of a local funeral home, she worked as a physical therapist, and they raised five children together, four of which played youth soccer.

When MLS came to town for its inaugural season in 1996, the O'Shaughnessy family bought season tickets almost immediately, becoming some of the first season ticket holders in team history. Margaret and Robert O'Shaughnessy attended nearly every home game together for more than a decade before his health began deteriorating while battling cancer.

On June 30, 2007, the couple watched the Crew face the New York Red Bulls from their seats in Section 123 at MAPFRE Stadium, with Robert in a wheelchair and connected to an oxygen tank to help his breathing. The Crew won the game, but Robert passed away a week later at the age of 62.

“He died one year too early to see the Crew win the MLS Cup,” says Margaret. “It was very bittersweet to watch them win after Bob was gone. After all the years of supporting the team, he would have loved seeing them win.”

When talk surfaced in 2018 of the team potentially relocating, three generations of the O'Shaughnessy family rallied with other fans behind a movement to successfully save the club. It was too crucial to the group —and especially to the late patriarch of the family— to let the team go without a fight.

“We weren’t going to go quietly,” says Margaret, who now has six season tickets in Section 124 so her family can attend games. “My son and his kids went to the rallies, we were chanting, ‘Save The Crew’ during the playoff game. This team was important to Bob, and it’s important to the entire family.”

"I want the parade ... I want the tears"

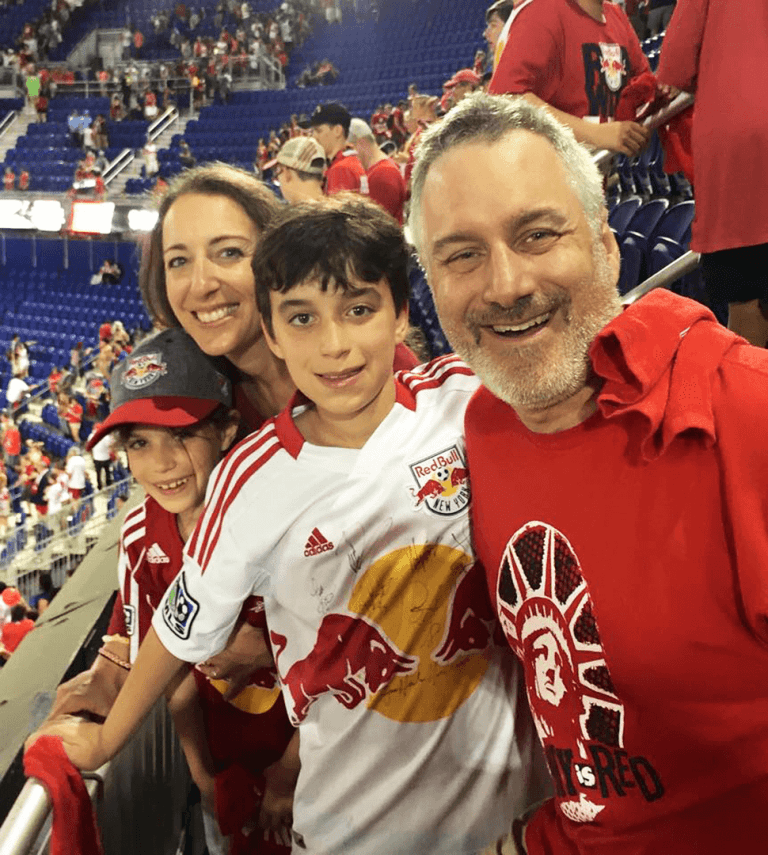

Mark Fishkin turned 50 years old last August, which means he’s spent roughly half of his life in a relationship with a soccer team that has, in one very critical way, never quite given him what he needs from a partner.

Fishkin knows the painful history of New York’s first MLS club as well as anyone. On top of being one of the club’s original season ticket holders from 1996—he used to trek from New York City’s Upper East Side to Giants Stadium to watch the MetroStars—he’s also hosted the popular and aptly named Seeing Red podcast covering the Red Bulls since 2010, watching up close as the club has come up short year after year.

The Red Bulls are, after all, quite famously the only original MLS club to never win a domestic cup. They’ve seen their fair share of luminaries come and go—Tab Ramos, Clint Mathis, Thierry Henry, Bradley Wright-Phillips—but Fishkin can just as easily rattle off the names of players who flubbed the big moment, fating the team to another offseason of despair.

While some of the new expansion teams have enjoyed playoff success in relatively short order, the Red Bulls have finished first in the Eastern Conference during the regular season six times since 2010, with not much to show for it except for a U.S. Open Cup final appearance in 2017.

“For better or worse, being a fan of this team is part of the identity you carry on your sleeve. It’s part of who you are,” Fishkin says. “Whether it was with your roommate in 1996 or with a family of four two decades later. There is a circadian rhythm to the entire process, that every year around this time there’s a thought of, ‘We’re getting ready to do this thing again.’”

But he’s determined to wait it out.

“I want the parade. I want the confetti and the tears. I want the moment that they finally [expletive] do it. I just hope it happens.”

"There were times I went by myself"

The total surpasses 400 and counting.

That’s the number of matches Mark Edson has watched through the various incarnations of MLS in Kansas City. But no season was tougher to endure than that inaugural year.

Back in 1996 the club struggled to sell tickets in the cavernous Arrowhead Stadium, the players donned rainbow-themed jerseys, and they went by “Kansas City Wiz,” a short-lived and openly loathed moniker that was dumped in favor of the Wizards after just one season.

Edson can admit it today. He went to a number of those early games by himself.

“There wasn’t much atmosphere. Some nights there were 4,000-5,000 fans, and we hated the name,” he says with a sigh. “It wasn’t like it was a Chiefs game, where if you had an extra ticket to the game, suddenly five people wanted to go. There were times when I went by myself because I just couldn’t find anyone.”

When the Wizards temporarily relocated to Community America Ballpark in 2008, Edson sat “on the first base side” near midfield, not far from where members of the local press and the broadcast team huddled in the press box. Edson would record the games and watch them after he returned home, often times hearing his own voice screaming at the referees on the broadcast because the microphones were so close to the fans.

Now a 46-year-old father of five and a UPS driver living in Lenexa, Kansas, Edson has some perspective on how far his club has come over 25 years. Following an emphatically successful rebrand in 2010 and a relocation to Children’s Mercy Park a year later, Sporting Kansas City have largely buried any sour memories from its first few years in the league.

“Soccer’s a big thing here now, and I don’t know if I ever expected that to happen,” Edson says. “My kids have never worried if the team would be here next season, or if they’d ever get a real soccer stadium. It’s so much different now. But the originals remember.”

"In the early days, fans going to games were pioneers"

Within just days of the birth of their daughter, C.J. and Stacey Napolitano faced a quandary unique to a certain sort of soccer superfan.

The couple’s beloved San Jose Earthquakes were hosting the Miami Fusion in the second match of the 2001 MLS Cup conference final, and they had no intention of skipping the game while stuck in the sleepy haze that sidelines most new parents.

“We got married and had a child a little bit older in life, so we sort of operated under the idea that our daughter Mia was going to fit into our lifestyle,” says Stacey Napolitano, a San Jose native. “We just figured she would do the things we do, which was a Quakes game. We asked the pediatrician and she told us to just put some cotton in Mia’s ears, so we went.”

Though Mia can be forgiven for having no recollection of the game—the Quakes won behind goals from Landon Donovan, Dwayne De Rosario and Manny Lagos at Spartan Stadium, and eventually went on to win their first MLS Cup title a week later—her parents haven’t forgotten. Most of the fans seated around the couple took turns holding the baby during the game, welcoming her into a family her parents embraced during the earliest days of the club.

C.J. Napolitano has been a San Jose season ticket holder since the club’s first game as the Clash in 1996, but the couple didn’t meet until two years later. On their first date he learned she was a soccer fan who had grown up watching the Earthquakes of the NASL era during the 1970s and 1980s, so their second date quickly became a Clash game in the spring of 1998.

“All my friends said, ‘Why would anyone want to go to a soccer game with you?’” says C.J. “In the early days, everyone who was going to the MLS games were pioneers. It almost felt like we were ambassadors for the game.”

The Napolitanos married in 1999 and have been season ticket holders ever since, despite the club’s painful three-year hiatus from 2005-2008. As the Quakes inched closer to the completion of Avaya Stadium ahead of the 2015 season, former club president David Kaval personally invited the Napolitanos to pick their seats for the new facility. In the years since they’ve secured enough season tickets to take their daughter Mia to games when she’s back in town from college at Cal-Poly San Luis Obispo, completing a circle they started 18 years ago.

“I still see people I grew up with, who I used to see at the old Quakes games,” says Stacey. “And now I see them and I see their kids, and they see me with mine. It’s like we’re part of a whole different family.”

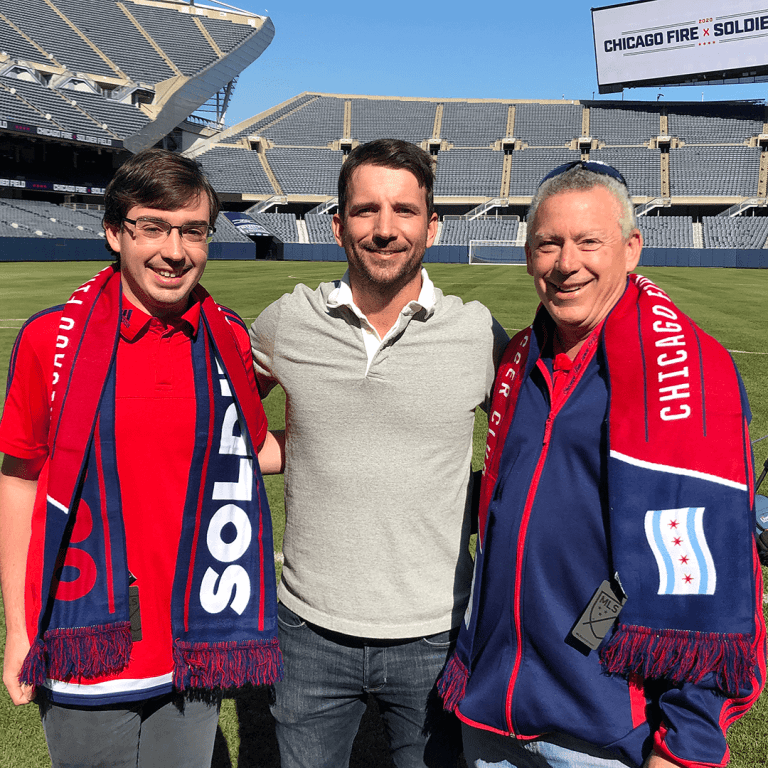

"Those are emotions that come with being a fan"

Daniel Kubick has followed the Chicago Fire from the shores of Lake Michigan to the suburbs of Naperville and Bridgeview, and back again. In that time he’s seen the club play for three different owners, a slew of club presidents and 10 head coaches, each tasked with bringing the city its first MLS Cup title since 1998.

And while the Fire are looking to break out of their longest stretch of futility in club history—they’ve played just two postseason games over the past 10 seasons, losing both—Kubick is quietly optimistic this year’s club is destined for something different under new owner Joe Mansueto.

“With a new owner, a new logo and headed back to Soldier Field, there’s just a different vibe right now for the club,” Kubick says. “You can tell [Mansueto] is sincere and he wants to bring something—or bring something back—to Chicago.”

The 57-year-old was the 213th person to buy season tickets when the Fire debuted at Soldier Field in 1998. He was raised on Chicago soccer as a youth player and a fan of the ill-fated Chicago Sting and Chicago Power, and then attended all six games played in Chicago during the 1994 FIFA World Cup, including the tournament’s opening match.

He went with his wife Anne to those World Cup games — she was pregnant with their first child at the time — but the Fire games belonged to his father-in-law. Alessio Mazzoni, now in his 80s, emigrated to the United States from Lucca, Italy in the 1950s and the two embraced the Fire together for years even as they moved stadiums, eventually landing at Toyota Park in Bridgeview beginning in 2006.

“I know he’s enjoyed it over the years,” Kubick says. “Even when they were struggling and it was hard to get fans out to Toyota Park. Obviously we both got frustrated, but those are just the emotions that come with being a fan.”

"We went there to watch D.C. United, that's all I needed"

When Audi Field opened in July 2018 it finally gave one of Major League Soccer’s most storied clubs a sparkling soccer-specific stadium to call home, more than two decades in the making.

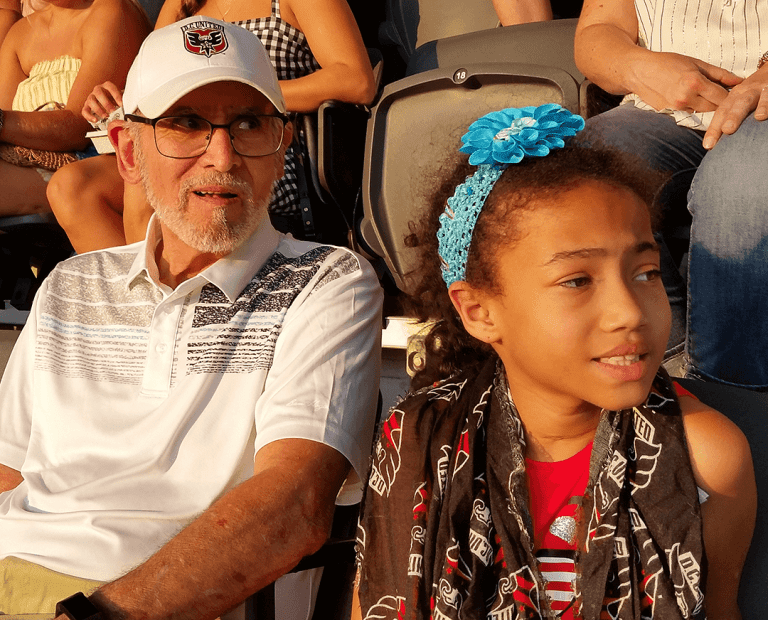

Mike Basileo, a 77 year old who spent four decades in the federal government, can appreciate Audi Field for what it symbolizes for his beloved D.C. United. But he still thinks fondly of the club’s old haunts at the beleaguered RFK Stadium, warts and all.

That’s coming from someone who in August 1999 watched a chunk of concrete fall from the underside of RFK Stadium's upper deck land “inches away” from the seat taken up by his son Christopher, who attended games with his father in those early days.

The Basileo family has an emotional connection with the old building. They first started going to games when MLS launched in 1996, thanks in large part to two boys who played youth soccer in Prince George County, Maryland. Years later, Christopher passed away from cancer at just 32. Basileo says the family never hesitated to attend games after his death, despite waves of emotion brought on by nearly every trip to RFK.

“It was hard to go down there without him,” Basileo says. “We sat in those same seats for years after Chris passed. But we just had to move on.”

D.C. United ultimately played their 347th and final MLS regular-season game at RFK Stadium in October 2017, drawing former players, coaches and more than 41,000 fans for an emotional farewell. Last year the District announced that it will raze RFK Stadium sometime in 2021 because it has “exceeded its useful life,” according to the agency.

“Obviously I like the new stadium, but RFK didn’t bother me in the least,” Basileo says. “I had a roof over my head when it rained, their hot dogs were pretty decent, and the beer was okay. We went there to watch D.C. United, that’s all I needed.”