THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's regular long-form series focusing on the biggest topics and most intriguing personalities in North American soccer. This week, Tim Froh digs into the unlikely story of a champion, the 1991 United States squad that lifted the first-ever Gold Cup.

Where's the bus?

Hours before their opening match of the 1991 Gold Cup, camped out on a curb in Los Angeles, Calif., the United States national team waited. The team bus, their ride to the Rose Bowl and a grudge match with Trinidad and Tobago, was nowhere to be found.

As kickoff drew closer, the players shared nervous glances. Would they have to forfeit?

Bora Milutinovic, the US’ feisty head coach, had seen enough. He was accustomed to the indignities of CONCACAF – decrepit facilities, lax security, questionable officiating – but for this to happen at home was almost absurd. He piled his entire starting lineup into the first few taxicabs he could flag down.

US goalkeeper Tony Meola, then 22, remembers squeezing into a cab with Milutinovic and four of his teammates, a helpless feeling overcoming him as the driver wove through dense LA traffic to deliver his passengers to Pasadena in time for the match.

One thought coursed through his mind: “God, this tournament has got to go better than this."

Two CONCACAF teams dominate the Gold Cup: the United States and Mexico. Read our interactive presentation about five matches that helped shape soccer in the region.

*

"Europe has its UEFA Cup, Africa has its African Nations Cup, Asia has its Asian Nations Cup, South America has its Copa America. CONCACAF had nothing. In April of last year, this was a dream. Today, this press conference on this tournament is the reality." – then-CONCACAF President Jack Warner, announcing the creation of the Gold Cup

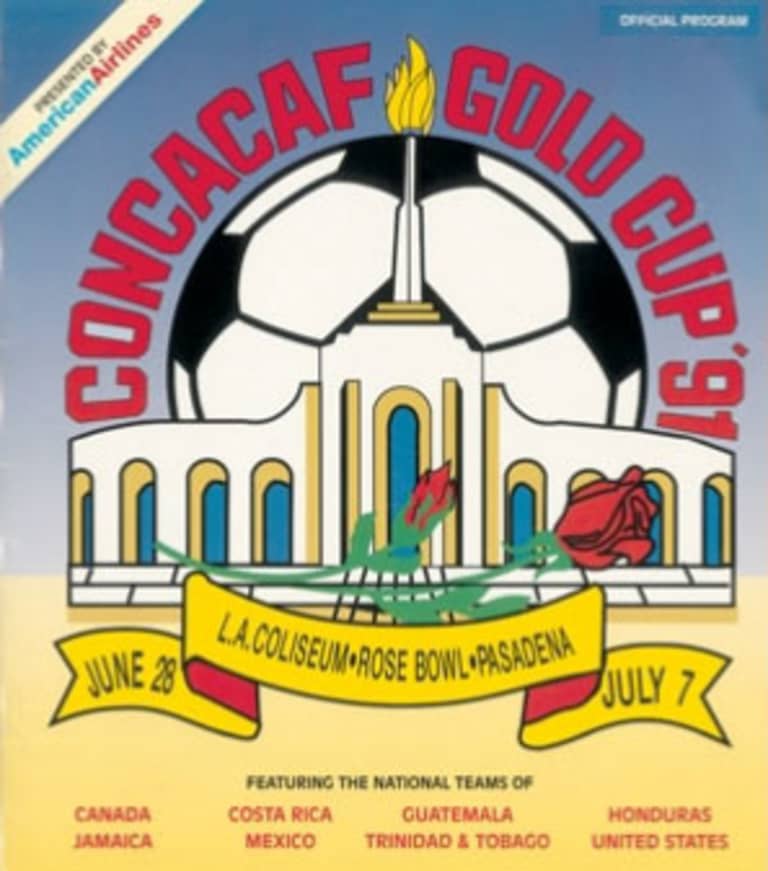

The Gold Cup was a new name for a familiar format.

The first CONCACAF Championship was played in 1963, hosted by El Salvador and won by Costa Rica. From 1973 to 1989, the NORCECA tournament (the acronym represented the regions entering the tournament: North America, Central America, the Caribbean), as it was also known, doubled as the final stage of World Cup qualifying.

But after the 1990 World Cup, Warner and general secretary Chuck Blazer dreamed bigger, setting out to organize a showpiece event for the region. U.S. Soccer, eager to show nervous FIFA officials and 1994 World Cup sponsors that there was a market for international soccer in Southern California, played host.

- Gold Cup 101: What it is and why does it matter

In 1991, the Gold Cup was held at two venues – the L.A. Coliseum and Rose Bowl in Southern California – between eight teams. It has since expanded to 12 teams, with games played in Mexico, the United States and, for the first time in 2015, Canada. All but three editions of the tournament (1993, 2003, 2015) have been played entirely in the US.

For an ambitious CONCACAF and suddenly relevant U.S. Soccer, the 1991 Gold Cup would be a laboratory in which to measure the popularity of the game in America.

Eight nations – Mexico, the United States, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and Canada – participated in the tournament, hosted that summer at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena and Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles, with $100,000 in prize money for the winner.

The decision was not without considerable risk.

Even Mexico, easily the most popular national team in Southern California at the time, consistently failed to draw sell-out crowds. Earlier that year, matches against the US and Canada, both played in Los Angeles, saw attendances that barely broke 5,000.

The US didn't fare any better. A meager 2,705 fans attended a March 1991 friendly against Canada at El Camino College in Torrance, Calif.

"[I]n the two countries where money for sports is abundant – the United States and Canada – soccer has been about as popular for spectators as hemorrhoids," a Los Angeles Times staff writer wrote in response to the announcement of the inaugural tournament.

The critics had a point.

After eight matches, average attendance barely edged over 10,000. Organizers blamed the local Galavision affiliate, which broadcast all the games.

"Live television was killing us," one tournament organizer told the Los Angeles Times. "Why should people pay to see games in person when they can see them live on television?"

Officials convinced the Galavision affiliate to black out live matches for the knockout rounds. To boost attendance, children 14 years old and younger were allowed in for free, filling in crowds that were far from pro-US.

This was the wild frontier of American soccer, but in spite of it all – even the team bus that broke down at the most inopportune time – the US managed to surprise everyone, including themselves, by winning game after game as they marched all the way to the final.

*

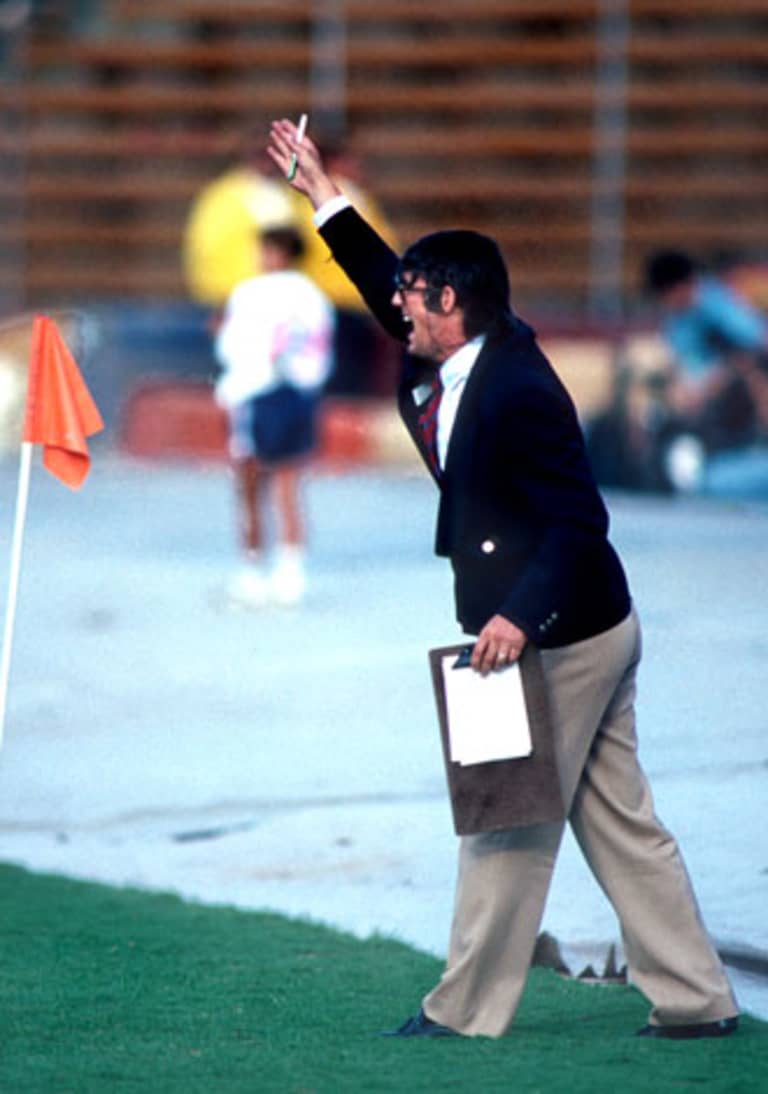

dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">Bora Milutinovic is one of only two coaches to lead five different teams at the World Cup (Mexico, Costa Rica, the United States, Nigeria, and China). He earned the nickname the Miracle Worker during a managerial career that spanned more than three decades. (Photo by dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">Daniel Motz/Motzsports)

*

"I remember him at one point telling us: 'You know what, the Mexican team puts on their shoes one foot at a time and the same with their shorts, they put on their shorts one leg at a time.'" – US defender Marcelo Balboa, recalling one of Milutinovic's team talks.

Following head coach Bob Gansler’s resignation in Feb. 1991, U.S. Soccer president Alan Rothenberg announced he was looking for a replacement with international experience to guide the American team into World Cup '94.

He didn’t have to look far.

In 1991, Milutinovic's stock in CONCACAF couldn’t have been any higher. The previous summer, the Serb took Costa Rica to the World Cup knockout stage and, in 1986, a Milutinovic-led Mexican team were a penalty-kick shootout from a World Cup semifinal. Rothenberg believed Milutinovic was the man to prepare the US for a World Cup on home soil.

- GOLD CUP BRACKET: Check out the road to the final

"Every national team he went, he made radical changes at places," Meola says. "You were on one side of that coin or the other and you wanted to be on right side, so everyone was trying to impress."

Multinovic had an impressive resume. He spoke Serbian, Spanish and Italian fluently, and was conversant in several other languages. English wasn't one of them.

Spanish-speaking defenders Balboa and Fernando Clavijo, among others, took turns translating their coach’s half-English, half-Spanish directions, a setup that was “definitely an awkward situation at times," says Balboa.

"Our pregame talks were just a comedy routine," remembers forward Eric Wynalda. "It was funny. We would just sit there and go, 'What did he just say?'"

Milutinovic knew he had his work cut out for him with the American team, but that didn’t stop him from trying to reshape an entire soccer culture despite a tenuous grasp of the language.

"The skill, the tactics is not so good," he told an interviewer before the 1991 Gold Cup. "But American boys in good shape, run all day. They never quit. That is good."

From his very first practice, Milutinovic set out to change the way the team thought about the game. At his disposal were a group of raw players – some of whom boasted only indoor soccer experience – and the Serb immediately went about molding them into professionals.

"Bora, he wanted everyone 24 hours a day thinking, eating, and watching soccer every day," says Clavijo, now FC Dallas’ technical director. "[It was a] different culture in the United States. It was shocking for many players."

No detail was too small, and no fundamental beyond examination. Former midfielder and forward Bruce Murray recalls an early practice in which Milutinovic interrupted a short passing drill to spend an half hour demonstrating the proper foot angle with which to strike the ball.

"There were no days off because the team was always in flux,” Murray remembers. “It was never like, 'Oh hey, you're it.' If Bora brought in a player he liked and he didn't like you or you weren't playing a lot, you were gone."

- CONCACAF Gold Cup: How to watch and follow the 2015 tournament

Milutinovic didn't just want to win, he wanted to build a modern soccer team – a patient, organized unit that could maintain possession and dictate tempo, neither of which were US strong suits.

"It was just different for us," Balboa says. "We were used to playing the ball in, the ball out, then we would hit a long ball up to the forwards. ... It was difficult trying to understand what Bora wanted."

Above all, Milutinovic wanted to change the team's attitude. More so than style, he knew, the US needed to develop a winning culture that could help carry the team, buoyed by home crowds and the opportunity to make history, to the knockout round of the upcoming World Cup.

"He was big on sports psychology," says Peter Vermes, then a US forward and currently Sporting KC’s head coach and technical director. "I think he tried to create a sense of belief around the group...that we can be good enough to play and win and not just play."

*

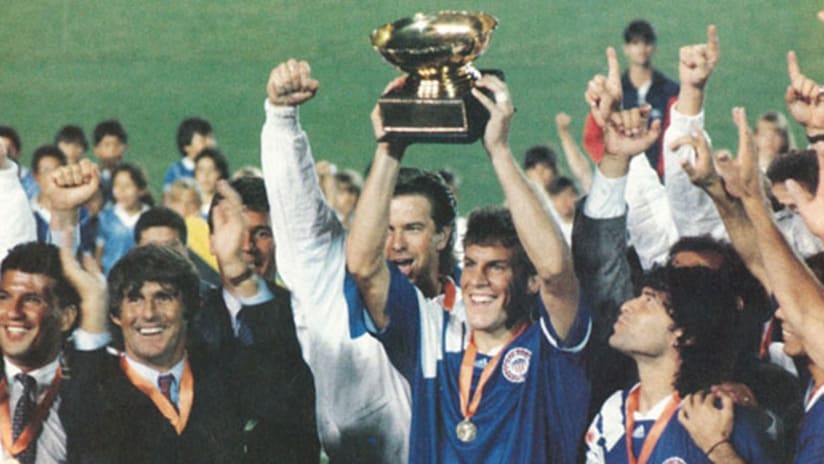

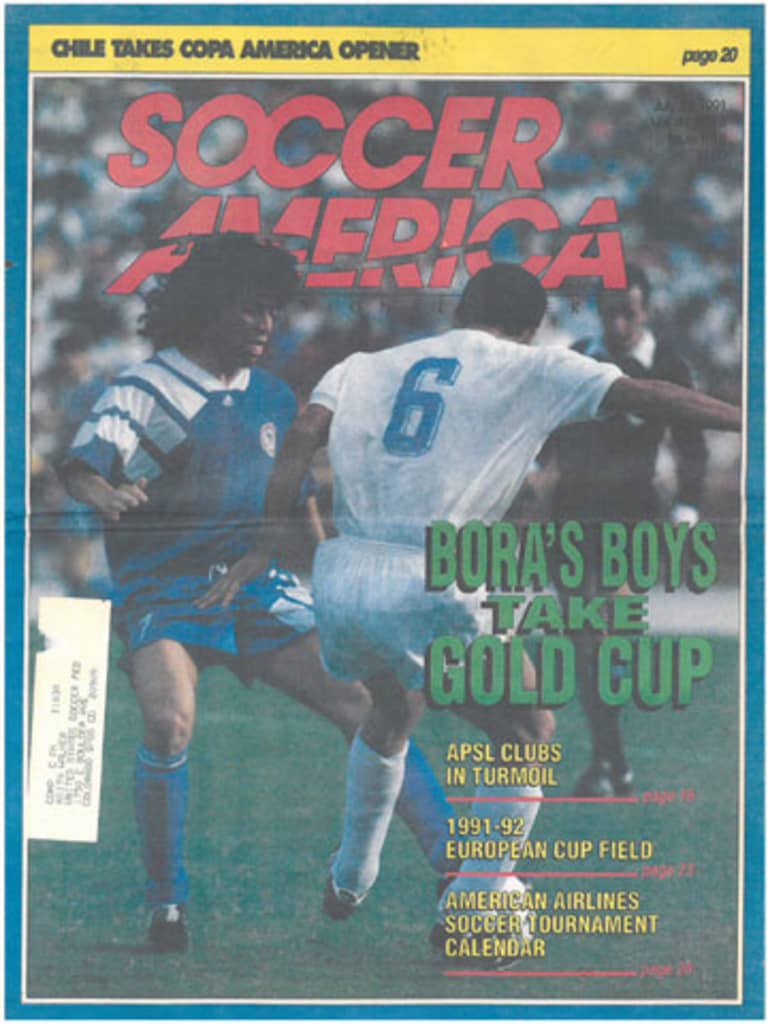

dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">Forward Eric Wynalda, in a pre-tournament friendly vs. Canada, was one of seven US players to score in the tournament. Wynalda, who played in three World Cups, retired the US' all-time leading scorer with 34 goals in 106 appearances, a mark that stood until Landon Donovan (57) passed it in 2007. (Photo by Daniel Motz/Motzsports)

*

"We almost blew it, too. We got there. We were totally unprepared. We weren't ready." – Wynalda on the US’ opening Gold Cup match

When the Americans finally arrived at the Rose Bowl ahead of their opening match against Trinidad and Tobago, the players rushed to the locker room. Quickly, they learned there was barely enough time to change, let alone warm up ahead of a match they knew would be a tough one.

The Soca Warriors sought revenge for Paul Caligiuri's "Shot Heard 'Round the World,' the goal that knocked Trinidad and Tobago out of qualification for Italy 1990 and delivered the US to their first World Cup in 40 years.

US striker and current FOX Sports pundit Eric Wynalda hurdles a challenge from a Trinidad and Tobago defender in the American's opening Gold Cup match. The team's bus failed to show, forcing the coaching staff and players to take taxicabs to the Rose Bowl. (Daniel Motz/Motzsports)

As the locker room convulsed with hurried preparations, Vermes noticed a smiling Milutinovic playing an impromptu game of basketball with a few wadded up balls of paper and a trash can. “This guy's crazy,” he thought.

Years later, Vermes understands what Milutinovic was doing.

"He was trying to take our minds off the fact that there was all this distraction and turn it into an opportunity for us to be relaxed," he says.

Whatever Milutinovic was doing,it worked. Despite the bus debacle and lack of a warmup, the US fought back from a one-goal deficit, breaking Trinidadian hearts again with goals from Murray and Balboa in the final five minutes of the match.

#USAvMEX comes to life in Five Finals, Five Stories

The late comeback and winner, a fortuitous bounce to Balboa setting up an overhead kick, was a critical moment in the team's ongoing evolution under Milutinovic.

"I said to myself, 'We can win any game. We don't have to worry – 85 minutes, it doesn't matter. We'll be able to figure our way through this,'" Murray recalls. "That just led us through the whole thing."

The US followed up by shutting out Guatemala, 3-0, behind goals from Murray, Brian Quinn and Wynalda. Then, in their final group game, the Americans knocked off perennial CONCACAF power Costa Rica, 3-2, in a wild, back-and-forth affair that saw the lead change three times.

"Nobody paid attention. Nobody gave us a chance," remembers Clavijo. "Sometimes we were not prepared, but with Bora we took every game with the possibility that we could win it."

*

dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">dlCatalogctl00lblImageCaption">Forward Peter Vermes, above, tied for the team lead with two goals in the tournament, production matched by Bruce Murray. The current Sporting KC head coach, who eventually made the switch from striker to center back, also scored the opener against Costa Rica in the US' group-stage finale, a 3-2 win. (Photo by Daniel Motz/Motzsports)

*

"We walked in knowing that we were playing the team that was supposed to reach the final. If I told you that we were prepared and we were confident, I'd be lying to you. I think we were all scared." –Balboa

Despite an unblemished start to the tournament – nine points that left them atop Group B – few gave the US much of a chance against Mexico, CONCACAF’s preeminent power and the Americans’ semifinal opponent.

Between 1934, when the first match in what became a historic rivalry was played, and 1991, the US won just twice in 25 tries. They hadn't beaten El Tri in any competition in 11 years.

But the ‘91 Gold Cup team was different: young players who brought swagger and an extra dose of belief that, despite long odds, they could do something few of their predecessors had done before.

"Bora made it clear that this was going to be the start of trying to get to the top of CONCACAF and that was mission number one: establish ourselves in CONCACAF," Meola recalls. "So the first order of business was Mexico, and to be ahead of Mexico. We felt that we could get it done."

Mexico, meanwhile, shrugged off talk that they were underestimating their semifinal opponent.

"Bora knows Mexico," El Tri head coach Manuel Lapuente told reporters before the match. "But Mexico knows Bora."

From the opening whistle, the match was a rough-and-tumble affair. The US, however, hung with Mexico. Despite playing the kick-and-chase style that they had been trying to shed, the Americans kept the game scoreless through the first 45 minutes.

Then, as the second half got underway, something clicked. The passing and patient build-up play that fueled their group stage success returned, and the US found themselves on the front foot.

"This is where the American team basically said enough is enough," remembers Wynalda. "We can play with you guys. And we're not going to back down. We're not going to be intimidated by the crowd. We're not going to be intimidated by anything. We're going to beat you tonight."

In the 48th minute, Balboa nodded down a Hugo Perez free kick and there, open at the far post, hovered defender John Doyle.

"There was a little window between the guy who was on the pole and where the goalkeeper was and I just passed it in to the goal," Doyle recalls. "It wasn't really any big deal, but it was neat to score against Mexico and go to the crowd of Hondurans who were cheering for us."

Meola remembers Doyle's goal as the moment when he finally began to believe the US might actually win the game: "We're thinking, 'Man, things must be good. John Doyle's scoring with his feet!'"

Balboa took a more cautious approach.

"It was, 'How do we hold on?'" he says. "That's just the honest truth."

Insurance came soon enough.

Hardly more than 15 minutes after Doyle's goal, Perez sent a ball into space along the right for Vermes to run on to. The New Jersey-born striker cut across the top of the box, beat two Mexican defenders and powered a thunderous, dipping left-footed shot up and over the outstretched arms of Mexican goalkeeper Pablo Larios.

Outplayed and frustrated, Mexico resorted to intimidation tactics – off-the-ball fouls, violent language and physical threats – in an attempt to throw the Americans off their game. Each time they lashed out, the US players responded with a smile

- Gold Cup: The 10 stars you need to know

"You can't lose your composure. You need to be classy. You need to smile at them, because if you smile you will scare them more than anything," Wynalda remembers Milutinovic telling his charges before the match.

In the final 25 minutes, the US wore down El Tri with fresh legs and frustrated them with possession.

"It was a very physical match, but we were fitter than the Mexican team," says Murray. "That's the thing I'll never forget because Bora used to run us to death. I remember looking up at [Mexican midfielder Luis Roberto Alves] at maybe the 75th minute. He's bent over, he's holding his shorts and I thought: 'I've got this son of a gun. He's done.' So I kept running him into the ground."

As the referee blew his final whistle and the US players celebrated on the pitch, the Mexican players walked back to their locker room in disbelief, the tens of thousands of El Tri fans at the Coliseum drowned out by the cheers of a small contingent of boisterous American and Honduran fans.

"It was a humongous achievement for us, knowing full well that now we had the chance to play in the final and win," says Vermes. "I think it was a major confidence-builder for the group."

"No one remembers that in the 1980 Olympics [men's hockey tournament], there was a final game. Everyone seems to think the game against Russia was it. The game against Mexico was kind of like that. We were simply fried." –Wynalda on facing Honduras in the 1991 Gold Cup final

The letdown was inevitable. The final was the US's fifth match in nine days and Honduras' fifth in 10. From the opening whistle, the two teams settled into a stodgy, aggressively physical stalemate.

"We were playing for penalties," Murray admits. "And so were they."

"They slowed the game down so much it was unbelievable," Clavijo told the media after the match. "They really didn't want to run up and down the field with us."

And so with both teams intent on keeping the clean sheet, to PKs it went. First on Milutinovic's list of penalty takers was defender Marcelo Balboa.

"I was like, 'Aw, crap,' Balboa remembers. "I'm thinking there are so many forwards and other players that could go before me."

As he approached the penalty spot, Balboa reviewed his plan: run up to the ball and smash it as hard as possible. If the goalkeeper could save that, then Balboa would at least know that he had forced the keeper to make a heroic save.

"I wound up and just hit the living crud out of that ball,” Balboa says, “and when it went in I was just like, 'Thank God.’”

Honduras' Juan Francisco Castro stepped up to the spot after Balboa's penalty and evened the score at 1-1, but the next four penalty takers – Vermes and Perez for the US, Marco Antonio Anariba and Gilberto Yearwood for Honduras – missed their shots. Caligiuri stepped up and slotted home his attempt to end the slide.

Once again, Honduras matched the US penalty-for-penalty, as Eugenio Dolmo Flores even the score at 2-2. US forward Ted Eck stepped up next to take the team's fifth penalty.

The US have won the Gold Cup five times, second only to Mexico's six titles. After winning the inaugural tournament in 1991, the Americans waited to lift the trophy for 11 years, then won four championships in their next seven opportunities.

"I remember practicing PKs quite a bit," Eck, now an assistant coach with Real Salt Lake, recalls. "All week leading up to those PK opportunities, I had a certain corner I went to and I played it there every time and I had success with it. That's why Bora chose me, because in practice I did quite well with it. But then, when I went to take the kick, I went to the other corner."

He missed.

"Bora was just so confused with why I changed, but I didn't really know myself," Eck laughs. "It was a split-second decision. As I reached back to strike the ball, I thought of going to the other corner, which was a mistake on my part."

The decision to improvise couldn’t have come at a worse time. Honduras could win with their next kick.

Penalty taker Antonio Zapata went for power, but unlike Balboa, he struck the ball with too much pace, sending it soaring over Meola's goal into the stands. Crisis averted.

Then, once again, the next two penalty-takers for both sides failed to convert. Clavijo had seen enough.

"I was really paying attention to the goalkeeper. The goalkeeper was jumping to one side way before each shot was taken," he recalls. "I made up my mind: I'm going to go to one place. I'm going to wait for the goalkeeper to jump and that's what I did.

“I didn't even hit the ball hard. I just faked when I was going to kick the ball and the goalkeeper moved to the right and I placed it to the left and the ball almost just rolled [in]."

The pressure was now on Honduras' Juan Carlos Espinoza. If he made his kick, the US would be forced to take another penalty. If he missed, he would become a national pariah.

Espinoza sent his attempt high over the crossbar. Game over.

In the midst of wild celebrations, the weight of the US’ accomplishment began to sink in. The craziness of the tournament – the bus fiasco, the comeback victories, the win over Mexico – had brought the team together, pushing each player beyond his limits, both mentally and physically.

"I just remember feeling like the national team was a group of guys that liked each other, would fight for each other, and just enjoyed each other's company," says Wynalda. "That team was all for one, one for all."

*

*

"You don't measure soccer in terms of one week." – Milutinovic, after the 1991 Gold Cup final

That Gold Cup victory was a watershed moment in US soccer history. It nurtured a sense of belief and purpose in a group that, two years earlier, had been ecstatic just to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1950.

"I think it taught us that we could galvanize as a group and win a big event," says Murray. "Bora instilled that. We didn't know who we were. We didn't have an identity. That [Gold Cup win] gave us an identity."

Since taking their first big step in 1991, the US have won four more CONCACAF titles and compiled a 30-1-3 record in Gold Cup group play. The Americans take on Cuba on Saturday in Baltimore (5 pm ET; Fox, Univision) as they chase a title that would tie Mexico for most all-time.

But the growth of U.S. soccer and its success on the international stage would never have been possible were it not for a generation of players whose self-belief and determination overcame what seemed like insurmountable odds.

"[The] Mexico [semifinal] was a little bit of a turning point with U.S. Soccer in that we felt like, ‘Oh yeah, we can win against Mexico,” Eck remembers. “’We can score goals against them. We can be better than them.’"

"In 1990, we taught ourselves that we could compete," Vermes says. "In 1991, we realized that we could win. We needed to have that feeling. They were both great stepping stones, but you have to do it in that order."