EDITOR'S NOTE: To mark the anniversary of Major League Soccer's first-ever game between the San Jose Clash and D.C. United on April 6, 1996, MLS YouTube, Twitter and Facebook channels will air the game at 4 pm ET this Monday. A part of MLS Classics: Remix, the enhanced broadcast will feature alternative commentary from MLS legends Eric Wynalda and Jeff Agoos, as well as current D.C. United goalkeeper Bill Hamid and MLSsoccer.com's David Gass. You can also now follow the @MLSin96 Instagram account, which will chronicle the entirety of the inaugural MLS season in “real-time” throughout 2020.

How much was riding on Major League Soccer’s inaugural game 24 years ago?

Consider the stakes: This was top-flight professional soccer’s long-awaited, highly-fraught return to the United States after an 11-year absence, the maiden voyage of a fledgling craft whose many predecessors had imploded, crashed, sank and otherwise disappeared with barely a trace.

“In the days leading up, it almost felt like walking on air,” recalled Phil Schoen, the play-by-play veteran on ESPN’s broadcast, “and I guess walking on eggshells. It just didn't quite feel real.”

The whole thing was running late, well behind the schedule FIFA envisioned when it made the league’s founding a condition of awarding the nation the 1994 World Cup. And it featured a tight salary cap and unprecedented new single-entity structure, intended to pool resources and risk, but also heavily scrutinized in the countdown to launch.

“The lead-up was really frantic in just a ton of ways … It was just an incredible amount of pressure. I think there was this collective sense that we all kind of had one shot at this,” Beau Wright, the first communications manager for D.C. United, who would bring MLS into existence with a visit to the San Jose Clash, told MLSsoccer.com. “We were the US’ new, professional, first-division league, and nobody wanted it to appear as if it was amateur hour.”

As D.C. president and GM Kevin Payne put it: “None of us knew what we were doing. At every level, it was trying to build a plane in flight.”

Or you could just measure it by the stomach-churning anxiety of the players themselves.

“The hardest part was getting the guys to just focus on the game,” said star Clash striker and US men’s national team World Cup hero Eric Wynalda. “We ate at the little Il Fornaio [restaurant] that's right down the street in downtown San Jose, and I remember they thought that the food was bad because four of our guys threw up after lunch. And it had nothing to do with the food. It was just nervousness.”

The final days were hectic and nervy. But San Jose’s front office had vital experience as members of the city’s hosting team in the World Cup two years prior, and Clash president Peter Bridgwater’s marketing efforts helped draw a sellout crowd. FIFA chief Joao Havelange was jetting in for the occasion, and the sunny weather was more than cooperative that weekend.

When Esse Baharmast, the game’s referee, did his usual pitch inspection the day before the match, the venue’s notoriously tight playing dimensions were deemed big enough, if barely. But what he saw at midfield nearly set all hell loose.

“The groundskeepers were working, painting this huge MLS logo in the center circle,” recounted Baharmast last week. “And by the FIFA laws of the game, there must not be any markings on the field other than the field markings.”

The top American ref at the time, Baharmast also oversaw MLS Cup, U.S. Open Cup and A-League finals that year, and made history as a standout at the ‘98 World Cup. He declared the logo had to go, despite Bridgwater’s pleas, or someone else would have to call the game.

“Oh my god, these f*ing idiots,” exclaimed United coach Bruce Arena in trademark style when he heard the news.

Spartan Stadium’s crew eventually broke out the green paint and started a coverup job, using a hue not too dissimilar from the one ESPN’s production crew insisted they use to minimize the appearance of the stadium’s light poles. Meanwhile, Payne was irate to be told that his United had to wear red shorts and white socks, rather than his desired all-black kit, in order to maximize contrast with the home side.

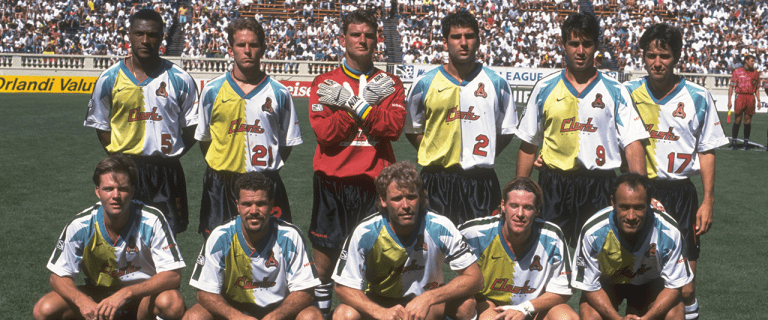

Why this matchup? San Jose offered mild weather, a solid soccer history and a promising team built around a core from the San Francisco Bay Blackhawks, a top side in the pre-MLS years. D.C. featured dashing USMNT captain John Harkes and Marco Etcheverry, the memorably mercurial – and mulleted – Bolivian playmaker.

“We had a lot of faith in Peter Bridgwater,” said Payne. “He was a promoter, and we'd been doing soccer games in that market for a long time. So there was a lot of confidence that he would get a very good crowd.

“Our team, the league thought that we would be good … We had Marco, who was a very well-known player and very distinctive, had that distinctive haircut. They had Eric Wynalda, who was a star with the national team. So I think it just made sense.”

Teams had just 18 roster spots each and were being built on the fly, with a rogue’s gallery of different personalities.

“There were some good players, and we had some national team stars,” reckoned Rick La Plante, Wright’s opposite number with the Clash and a sportswriter before that, “but the back end of everybody's roster was like ‘ehhh, hope we don’t have to use this guy.’”

Anticipation and fear hovered in equal proportions. The players and coaches knew the stakes as well as anyone, and many had scant experience with the type of demands being placed on their shoulders. Preparations were imperfect for both sides, to say the least.

“We had an awkward preseason,” Arena, now the New England Revolution head coach and sporting director, said.

As thoroughly as he’d dominated NCAA ball at the University of Virginia, Arena had never coached at the pro level before. And for the first half of the year, he and assistant coach Bob Bradley juggled their United duties with leadership of the US men’s Olympic team.

An endearingly unorthodox character, “El Diablo” Etcheverry reported for duty overweight – “Marco was not the fittest person in the world. Marco was good for like, firing up a steak at 11 o'clock at night,” recalled United administrator Ray Trifari with a chuckle – and future club icon Jaime Moreno wouldn't arrive from England’s Middlesbrough until midsummer.

Meanwhile, the Clash were rocked by the sudden death of the wife of showcase import Michael Emenalo – an inspirational presence who 15 years later would become technical director at Premier League powerhouse Chelsea FC – during preseason.

“With all these great signs pointing to a new league, there was some tragedy behind the scenes,” said midfielder Paul Bravo.

Many of the players were familiar with hard-charging English coach Laurie Calloway from the Blackhawks, but his fraying relationship with Wynalda would soon become a flashpoint. And they had nothing remotely like the cutting-edge training facilities today’s MLSers enjoy.

“We had like four different practice spots,” said Clash defender John Doyle. “One of them was Morgan Hill, which was a youth facility that we drove 45 minutes to get to – changed at Spartan Stadium, drove 45 minutes in our own cars, practiced, drove back, showered and went home. That was normal back then.”

For all that, Doyle and his fellow domestic players were grateful for a chance to play in a top league of their own. And thanks to the beautiful game’s tumultuous history on these shores, the big day at Spartan Stadium was not only the first impression for a new league. It was also a reintroduction of an entire sport to the greater consciousness of an American public whose interest was, even after the runaway success of the ‘94 World Cup, no sure thing.

"What today's reader might not appreciate was the almost vacuum that we were in regarding soccer in this country,” noted La Plante. “How do I put this? The ignorance of the game was huge … Americans just didn't care about soccer. There was almost a level of, I wouldn't call it disdain, but close to disdain for the sport. People said, ‘we got baseball, basketball, football, a little bit of hockey – what do we need with soccer?’

“So for those of us who love the game, that brought just such a measurement of intensity to the launching of MLS in general and to that inaugural game in particular … Everybody's worst nightmare was a scoreless tie.”

Along those lines, some executives paid the players an unexpected pregame visit. “One thing that definitely stands out is having the league officials [like] Sunil Gulati coming in the locker room, which was basically a little trailer behind the stadium, and wishing everybody good luck,” said D.C. goalkeeper Jeff Causey. “The one thing he said to me was, ‘we're hoping that this is a high-scoring game.’ I remember thinking to myself, 'If this is a high-scoring game then I don't have a job tomorrow.'”

Would everyone handle their duties? Could the game itself live up to the enormity of the moment? More than 31,000 curious spectators and more than 100 journalists would flock to the corner of South 7th Street and East Alma Avenue to find out.